TrustNews Sep 22

A Royal Palace for Charles II

East elevation of King's House. Drawing by R. Baker

Early in the 1680s, the City Corporation placed an advertisement in the London Gazette promoting the attractions of Winchester and the nearby racecourses at Worthy Down and Stockbridge Down. Charles II was an accomplished horseman and had a palace at Newmarket, which burnt down in 1683. The King made his first visit to Winchester in 1682 and the City offered to sell the site of the former Castle and surrounding land for five shillings, for him to build a royal residence.

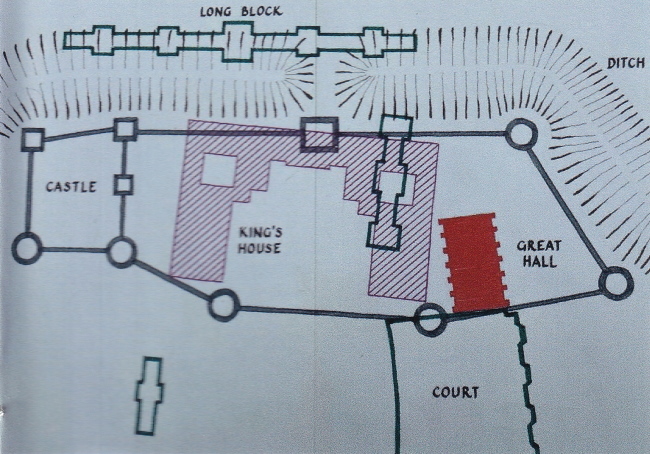

The King instructed Sir Christopher Wren, Surveyor to the King's Works, to prepare plans. He sited the Palace to the south of the Great Hall, on an east-west axis, aligned with the west front of the Cathedral. An agreement was made with the Justices of the Peace, responsible for the Great Hall, that it be demolished and a new hall built elsewhere. This would release land to create an access from the High Street for horses and carriages to the grand courtyard in front of the Palace.

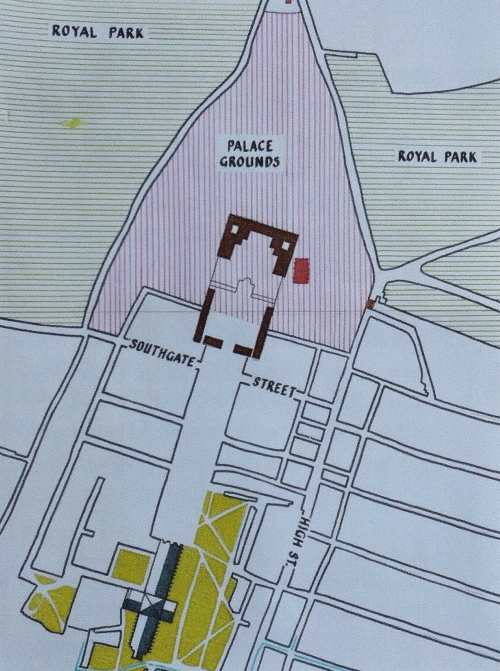

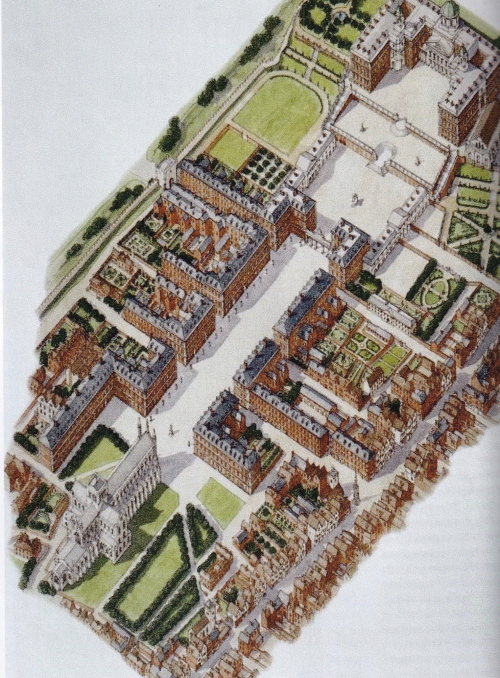

On the eastern, city side of the Palace a grand avenue, cutting through Southgate Street, St Thomas Street and Little Minster Street, was to lead to the Cathedral, and be lined with new three storey buildings to accommodate the court of the King.

Plan of King's House and the Castle. Drawing by R. Baker

On the west side of the Palace, land on West Hill was to be used for Palace Grounds, with a Royal Park to the north over Oram's Arbour and a Royal Park and Hunting Grounds extending south down Southgate Street to what is Stanmore Lane today, and up to Romsey Road.

Work on the Palace, also known as the King's House, started in 1683. By 1685 the walls, floors and roof of the building were completed. Charles II died in 1685, and work on the Palace was halted by James ll. The project was finally abandoned in 1687. The need to implement the deal to demolish the Great Hall in return for a new hall was not required.

The built shell of the Palace was used as a prison and barracks, until it was destroyed by fire in 1894. Fortunately, firemen were able to save the Great Hall from the flames of the nearby Palace building.

Plan of Palace and Park and the avenue between King's House and the Cathedral. Drawing by R. Baker

Had the plans of the King and Wren been realised, the form of Winchester's development as we know it today could have been very different. Could the railway company for the London to Southampton line have been able to give any thought to making a survey for a line through the Royal Park and Palace Grounds? Would their only option have been to take a line to the east from Kings Worthy to Chesil and Shawford? Then, instead of Winchester expanding to the west, development of houses, schools, a hospital and prison would ascend the slopes of St Giles Hill and onward to the east, towards Morn Hill. With the royal presence to the west, the protected open countryside could today be a National Park.

The small-scale street pattern created by the Romans and the Saxons and the Cathedral Green and Close are core components of Winchester's conservation area. The grand scale planning of an avenue between the Palace and the Cathedral, shown in the conjectural drawing made by Stephen Conlin based on research carried out by Simon Thurley, the former head of English Heritage, would have given the centre of Winchester an entirely different character to the one we have today.

Conjectural view of the Grand Avenue. Artwork © Stephen Thurley. Commisioned by Country Life Magazine