Winchester Preservation Trust AGM - TrustNews Spring 2000

The speaker at this years AGM, Robin Nicholson, CBE, RIBA, was invited to address the topic, 'What Makes a Good City' because it is the fundamental question we face in every aspect of our concern for the future of Winchester. A better understanding of the qualities of the Good City would help guide both specific issues such as the Friarsgate development as well as wider policies about accommodating the growth of the City, but as politicians say, the fact of the matter is, those qualities are complex, difficult and not well understood by anyone, least of all those who have the power or authority to implement change, and especially developers. We hope that this talk will be the beginning of a continuing debate which will take us toward a better understanding of how to form the future of the City.

The following are edited notes of his talk.

"I have been asked to speak about what makes a good city. This debate is not new; indeed it has been raging in different ways since the foundation of Athens.

What is the problem?

Trondheim Regional Hospital, Norway

There is a new urgency today because a number of incompatible habits in the way that we live vie for supremacy:

- The highest percentage of home ownership is houses on their own plots, which leads to low density sprawl.

- The continuing growth of car ownership coupled with a right-to-drive everywhere culture.

- The collapse of the fine long-standing Christian obligation to protect the weaker members of our communities.

- The Kyoto Protocol requiring radical reduction of gases mainly generated by our chosen forms of transport and our existing housing stock.

These are not simple matters. Those four issues could have been offered to you as one half of a set of dialectical pairs, which might have produced the following questions:

- What kind of homes do we want to live in and does the present market offer them? Do we like living in miniature mansions or beastly blocks of flats, both types struggling to attain respectability by having screwed-on gratuitous pseudo-classical porches and pediments?

- Why do we all want to own cars just to watch them gently rusting on the street unused for most of the time? - [I recognise that this is a different issue for women and men!] Perhaps there is an alternative model, in addition to good public transport, like the Edinburgh City Car Club which provides easy access to a car at a much lower cost than straight ownership; they find they need 1 car between 4-6 households and are recording a 50% reduction in car use.

- Where will single people and young couples live, and where were all the homeless before they started begging on the streets?

- What if estate agents were obliged to include, within their fairly outrageous fees, an energy audit for the incoming tenant/purchaser? Coupled with carbon trading, all of a sudden, energy conservation could become something we could all identify with, and even make money!

To these we might add a fifth question... Can our existing planning structures cope with the need for an increasing understanding of the increasingly complex functioning of cities?

What is urban design

Talking about cities is, as you know, not just a question of the quality of the street furniture and the simplification of the signage jungle. Cities came about to enable exchange;

- Social exchange

- Commercial exchange

- Cultural exchange

University of East London, Dockland Campus Scheme

Thus urban design, only part of which springs from the fine post-Renaissance skills of composition, which we abandon at our peril, has come to its next age by recognising that it needs to bring together

- Political leadership

- Economic management

- Cultural entrepreneurship

- Spatial composition

Lord Rogers:

How can we improve the quality of our towns and cities?

Towards an Urban Renaissance

The Rogers report considered these issues in an impressively, rounded way, so all encompassing that it is no wonder that we still don't have the White Paper. The task was to consider "how we can improve the quality of both our towns and countryside while at the same time providing homes for almost 4 million additional households in England over a 25 year period".

During this session we can only consider some aspects of this exciting new challenge: well perhaps not exactly new but one with much greater political support and a more comprehensive approach than on previous occasions. Even if Government is struggling, it is trying to be joined-up in its actions, and the Treasury is talking with and appearing to listen to the construction industry for the first time ever. And we have a prime ministerial commission to get the best out of the opportunity.

Change

We are all struggling with the increased speed of change—yesterday it was the telephone, today it is the mobile telephone with built-in computer, e-mail and fax.

Margaret Thatcher introduced a root and branch radicalism that some of us found seriously uncomfortable while others cheered and many grew rich quick. Now, New Labour has seized the opportunities of a change culture to challenge many of our long-held assumptions and the pace is even more demanding. We have to have a balance between continuity and change — valuing the best of the past but recognising that many of the 'good bits' only came about through radical intervention in the past.

I know that we all feel threatened by the new technologies. I can no longer draw, in so far as I cannot draw on a computer. I did however very happily type these words on a laptop in North Norfolk at the week-end and send them down the normal telephone line to be printed in my office in London. Some would argue that, by eliminating the need to meet to speak, signals the end of cities while others point to the social energy generated by, what I consider doubtful, new enterprises such as cyber-cafes.

Winchester

I understand that the Trust is also changing and that this is leading you way beyond preservation towards trying to 'guide the quality of change'. And I salute this ambition.

I will show you some work that we did in Winchester but first I need to try to put myself in your shoes. Winchester is clearly a special place, but so are Blackpool, Bath and Bournemouth, each in their own way. While I understand and support the perceived imperative to preserve the history of Winchester, surely we must also support positive change, accepting that there will be risks, if we are to retain the energy that created that history in the first place; this cannot, however, be the same energy since the power of the church has so diminished. The failure to realise that change is itself essential for the very preservation of that which we love, is surprisingly prevalent. On this I speak as a member of the strongly preservationist Highbury Fields Association in North London, where I live in the heart of an outrageously daring 5-storey speculative development built in open countryside in 1770.

I was reading at the weekend the results of some research that 'conclusively' shows that the defensible space theory and the resultant police programme called Secured by Design are completely flawed; in its place they suggest that the traditional fairly high density urban terraced street, with full 'permeability' for cars and pedestrians, is the safest. Living on Highbury Place, on the main pedestrian route from the underground station to the Arsenal, this comes as no surprise.

Nearly all of our work in Hampshire in the 1980s, was based on trying to turn existing object buildings into a framework of public spaces.

... At Winchester College we converted the gym into a theatre with a great porch that addressed a future cultural square. Then we stripped William White's heroic but redundant sanatorium back to its original core and linked the two halves with the suspended jewel box gallery to make the new art school.

... At Fleet Calthorpe School we added sun-shades over the windows in order to make it less uninhabitable; then placed two new buildings at right angles and planted a landscape so as to begin to create a series of useful spaces.

As architects we are constrained in what we can do to create the new city, but overcoming our natural inclination to design buildings as egotistical objects is critical.

Thus I have five messages this evening for those of you who are interested in tomorrows Winchester:-

- The new sources of urban energy must be identified and promoted since the decline of religion and traditional market shopping have weakened the city; I refer to health, knowledge and cultural exploration.

- The community must actively engage in the formation of their environment, but in order to exercise this constitutional right to participate, the study of architecture and cities needs to be part of the school curriculum.

- The obligation of buildings to make useful places must take precedence over the conventional lazy fixation with the appearance of the building.

- When it comes to inserting buildings into a fine historical context, compositional contrast is usually more successful than an attempt at sameness, which tends to diminish the value of the original.

- In all this there must be strong political leadership with the active engagement of the officers of the local authority. In Hampshire the fine example of Councillor Emery-Wallis is fresh in our minds.

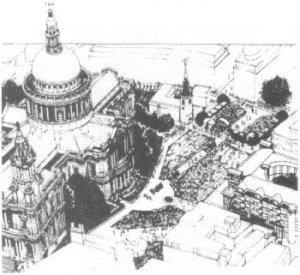

Petershill: proposal for pedestrianisation the Cathedral approach

Robin then described three recent schemes of the practice.

- Petershill in the City of London

- Trondheim Regional Hospital in Norway

- The London Docklands

Petershill, next to St Pauls, is a proposal to replace the dismal traffic oriented approach to the cathedral with a piazza for both the ceremonies and day to day needs of tourists.

The scheme for Trondheim Regional Hospital demonstrates both the powerful potential of health and university buildings to provide the energy that urban redevelopment needs, and the how the city can take the lead, by assembling land and promoting such a strategy. Our proposal was centred on a new public colonnaded city square with the four sides being connected below ground for servicing and at first floor level for patients and visitors. This allowed the best of their existing buildings to be incorporated and reconnected.

University of East London Docklands Campus

The Royal Albert Dock was the largest in the world when it was built but was abandoned in the 1970s and the dock buildings removed. The early proposals for a shopping centre were scrapped in the 1991/2 recession and the idea of using Higher Education to act as the honey-pot for other development caught on. Docklands Light railway feeds straight into an oval pedestrian forecourt with the student union and a convenience store from which a public right of way slopes up into the main University Square and on to the great lawn in front of the dock. The main auditorium, the local radio station, the print shop, the bank and various cafes and bars are gathered around the colonnaded square, and the Muslim prayer room.

Conclusion

I understand that you have some large projects already planned or under construction and you are, of course, under enormous pressure to play your part in the provision of 1.1 million homes in the south-east.

We tend to approach all issues from our own perspective; however one great change is that sustainable urban design %If requires a multi-disciplinary approach with the full engagement of the community. So, to avoid the lowest common denominator the game is to aim high. I would like to leave you and your City planners with four questions:

- Do we need elected mayors in order to provide more focussed political leadership?

- Can we expect good quality architecture, without a respected city architect?

- How can planning departments be more than tick-box bureaucracies, necessarily focussed on meeting the lowest common denominator, unless they encourage and actively engage in spatial and three-dimensional design?

- What needs to be done to ensure that your peers in the Winchester of 2099 will pay tribute to what you have added to your great city?

May I wish you well in the struggles for tomorrow's Winchester.