This article is reproduced by kind permission of the CPRE from the autumn edition of their publication "Countryside Voice"

Streets ahead - TrustNews Dec 05

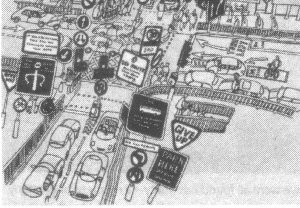

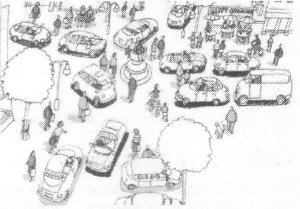

These two cartoons contrast the conventional and shared space approaches to handling traffic in the public realm (by the author).

The response of the majority of highway authorities to problems of traffic and speeds is to add more signs, signals, barriers and road paint. But there is another way says architect, urban planner and transportation specialist Ben Hamilton-Baillie.

It is a rare and exciting moment when a new set of insight and ideas changes the way we think about our surroundings. It is especially rare for a fundamental paradigm shift to be inspired by a traffic engineer. Highway engineering is not a profession renowned for radical insights or counter-intuitive challenges. But the work of Dutch traffic engineer Hans Monderman represents a very radical change in our thinking about the relationship between people, places and traffic. It is a change that offers new hope for the quality of towns, villages and rural roads.

The last time traffic engineering set a new agenda for our towns and cities was in 1963. The late Colin Buchanan's Traffic in Towns report for the UK Government concluded that civic life was fundamentally incompatible with the movement of motorised traffic, and it should be the task of planners, architects and engineers to segregate vehicles from pedestrian movement and social activities wherever possible. Segregation of the built environment into 'highway' and 'public realm' became the central dogma of traffic design across the UK and in other countries.

Hans Monderman was appointed Head of Road Safety for the northern provinces of The Netherlands in the 1980s, and given a wide brief to tackle rising pedestrian casualties in towns and villages. Having studied accident reports and conventional traffic engineering for many years, he realised that something was fundamentally wrong. As he describes it: 'when faced with a safety problem, most engineers tend to install something additional. My instinct is always to take something away.'

His early experiments in removing signs, signals, barriers, kerbs and road markings proved remarkably successful. Starting with small towns and villages across his native province of Friesland, Monderman inspired scores of public realm designs that allow vehicles and people to mix together safely, turning Buchanan's admonition on its head. By emphasising context and deliberately integrating drivers into the social and cultural world of the town or village, Monderman found that he could radically reduce speeds, improve safety and transform the quality of the built environment without limiting or restricting the flow of traffic.

Such a revolution rarely comes out of the blue. Monderman's 'shared space' principles have their roots in the pioneering work of Joost Valid and his contemporaries who introduced the woo nerf concept to European street design in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In more recent years, we have seen limited experiments in Norfolk villages (the work of Neil Mayhew) and across Wiltshire's settlements involving the removal of signs, road markings and conventional traffic calming to achieve slower speeds and safer roads. Monderman and his colleagues are building on the increasing realisation among behavioural psychologists that driver behaviour can be transformed through a strong emphasis on distinctive context. Signs and highway clutter appear to act as a barrier to reading contextual clues. Without them, drivers have to rely on normal cognitive skills to read their surroundings for clues, and the resulting lower speeds appear to reduce congestion by allowing road junctions to work more efficiently. Sharing Space Monderman's work is merely the leading edge of a seachange taking place throughout Europe in the use of urban design to inform traffic movement. Similar successful schemes can be found in Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Spain and Sweden. Sceptics assumed that shared space would only work in the bucolic, sleepy village and rural roads of pastoral Friesland or Norfolk. But more recent urban schemes in Amsterdam, Copenhagen and Groningen indicate that a reduction in highway clutter, barriers, traffic signals and road markings might hold the key to tackling serious congestion as well as road safety. In the industrial town of Drachten, a busy intersection handling over 22,000 cars, buses and trucks a day has been transformed by making a simple roundabout an integral part of the town's public realm.By encouraging human activity close to the junction and relying on eye contact rather than conventional pedestrian signals and signs, traffic queues appeared to have diminished, safety appears to have improved, and a busy piece of highway has become a lively and distinctive part of the urban fabric.

Hans Monderman's insight stems from a recognition from behavioural psychologists that single-purpose motorways and high-speed highways demand different cognitive skills to the complex human context of public space. The former requires standardised, simple, repetitive signs and signals. But if you treat the driver in the public realm as an idiot, you will foster idiotic driving. So a sign that reads 'Caution Beware of Pedestrians' in a town centre is not only patronising to the driver's intelligence; it also makes him less responsive to the normal human responses to places and circumstances.

The UK has begun to respond, albeit slowly, to the potential benefits offered by shared space principles. Shrewsbury High Street is one example where the usual manifestations of highway design have been removed to allow traffic to flow freely through a busy shopping area. There are ambitious schemes in preparation for Exhibition Road in Kensington, London - fronting the great Victoria and Albert and Natural History museums - and the New Islington regeneration area in inner Manchester based on shared space principles. But the majority of highway authorities still prefer to add rather than to take away.

CPRE has been campaigning relentlessly to reduce clutter and preserve the distinctiveness of towns, villages and rural roads. English Heritage's Save our Streets campaign tapped into growing public disgust at the damage done to historic environments through clumsy standardised highway engineering. Hans Monderman's inspiring examples suggest that this is not merely an argument about aesthetics. Ensuring that traffic signs, signals, road markings, kerbs, bollards and barriers are removed from towns, villages and rural lanes and confined to the high-speed highway network has more pragmatic benefits. It may provide the solution to the Government's key transport objectives of tackling congestion, maintaining access and improving safety.

Hans Monderman's traffic engineering emphasises the spatial qualities of place over the linear characteristics of the highway. This change challenges most of the regulatory framework and conventions within which UK highway authorities work. The Department for Transport promises a new Manual for Streets to respond to new findings on shared space. But new regulations are not likely to spearhead a change which is in essence about the removal of regulation. By treating the driver as an intelligent being, and as an integral part of the social and cultural fabric, shared space transfers the responsibilities and control of movement and traffic from the state to the community and the individual.

Such changes are rarely led by the state, but emerge from the growing confidence of communities to reject the standardised traffic engineer's handbook in favour of designs built on the distinctive history and circumstances of each town, village and landscape. The success of Monderman's schemes that apply such principles suggests that a revolutionary opportunity is available for those passionate about the quality of the urban and rural landscape.

Left: A sketch of Hans Monderman,

courtesy of David Engwicht (from his

forthcoming book Memo/Speed Bumps).