Ray Attfield enters the 'style and authenticity' debate - TrustNews Jun 18

This is an extended version of the article which appeared in the printed TrustNews.

John Hearn opened this long overdue debate with a plea: ‘It’s important to design for today and not attempt to recreate the past.’ I join it with the aim of looking behind the facade to see what provokes such strong reactions and why the focus on style rather than substance will damage the quality of the city.

One thing is clear: style is not the real issue, just a convenient label, the outward sign of common agendas, sometimes founded in faith or philosophy but more often on fashion and undefined likes or dislikes. Style is also political, complex, contentious, easily misunderstood and frequently used to seduce or mislead. There is no style which defines good architecture of now. What should determine the future of our towns however, is a duty of care, a responsibility to understand, and this to be founded on more than personal taste or outward appearance.

Words are too often used to suggest what is not possible and the real issues of this discussion are I suggest hidden within these key words: fear, tradition and traditional, modernity, context, authenticity, and honesty.

The first is fear, the quite normal fear of change, of growing up, of growing old, of the new, of the future. What we grow up with is familiar, we have formed our character within its comfort, but it is the past and we have no choice but to move into the future, to grow up. The desire to hold onto the past is understandable but the future can only be different. With reason we hold onto images, objects, memories, patterns of behaviour, even buildings because they provide an important foundation for what lies ahead, but facades of good breeding conceal a terror of ageing and death. The question is how to form the future with what defines the reality of the present?

The second is tradition. A tradition is a pattern of behaviour, passed down within a group or society, with symbolic meaning or special significance and with origins in the past. To be credible a tradition will reflect a significant aspect of life such as belief or good practice. Traditions which have lost their meaning, or are invented in support of fantasy or wish fulfilment, are hollow and nothing more than historical re-enactment, like the ‘Medieval Fayre’ which is taken down at the end of the day; they cannot fulfil the dream but worse they deny the possibility of achieving a better future. If we are a society which seeks not change but stability, the worship of tradition and settled order only makes the new more disturbing and we, less able to accommodate it.

Traditional architecture. What is it? A method of building based on local craft which no longer exists? Particular decorative features? Is it just a collective term for the complexity of the past? Or if the term is used, is it to pretend that nothing has changed, and is that honest?

next Modernity, the continuing project of the European Enlightenment and the foundation of our culture. It contains the idea that rational thought and change are essential to our existence in the real world. The process of change and a commitment to achieve its benefits still remain the foundation for good design. Modernism, the style of the early 20th century (now historical), embodied the principles of modernity. It incorporated classical ideas of proportion, scale and order, used rational rather than emotional criteria, and saw change as desirable, not something to be feared.

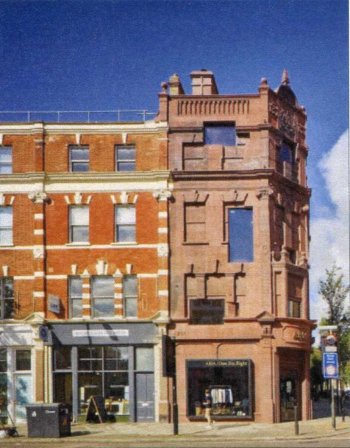

Context. All good architectural practice will be based on understanding and developing the real physical and spatial context not merely the visual, which can only create an external likeness to what exists, and though touching our sensibilities may mirror what would better be changed. The example by Amin Taha (fig 1) demonstrates an intelligent understanding of the complex question ‘what is an appropriate response to completing a 19th century street facade’ while still honestly and imaginatively saying this is of today.

Robert Adam used the term ‘Modern Contextual Architecture’ to describe the ‘classically’ detailed scheme in Southgate Street, and while I know of his playful sense of humour, for all the reasons I have given, such use of language is intellectually dishonest. When language abandons meaning, all manner of things appear possible.

Authenticity concerns being truthful, seeing reality for what it is, even if different to one’s own viewpoint or preferences, and coming to terms with, not avoiding the consequences. Authenticity is about honesty but is frequently undermined by mimicry on which Pope Francis said recently: ‘Mimicry, that sly and dangerous form of seduction that worms its way into the heart with false and alluring arguments.’

We have a responsibility to carry the past into the future without trivialising it and a responsibility not to raid the classical foundations of European culture for quick fixes and decorative gestures.

The familiar is of the past by definition, but there cannot be change – and change there must be – without creating the new. If fear of the new is the issue then we must be mature enough to understand and guide it, not hide behind a facade deceitfully giving the appearance of having not changed, and avoiding the potential benefits and qualities which only change can provide.

While style is not the issue, its examination reveals critical contradictions and differences, in particular the opposites of rationality and romanticism. These two ideas of reality will each have elements of the other and constitute part of everyone’s understanding but are non the less polarised views which explains why evaluating what is good design is difficult and complex. Rationality is however, a value held in common and basic to western civilisation, whereas the romantic expresses the personal and emotional; surely there can be no question that the rational approach must define and give form to what is to be built in the future. The romantic side will have its place but as personal expression not as the determining framework of the public realm.

Not surprisingly the Romantic view is the more popular position, and easily seduces opinion away from rational interpretation, with picturesque styles and comforting language that is at worst deceitful, or at best encourages misunderstanding.

In this light it is really disturbing to find in the vision for the Central Winchester Regeneration Area, that rationality seems to have been abandoned for romantic wish fulfilment, with expectations raised on the basis of marketing language, much like the promises of ‘a healthy life’ on the back of cereal packets.

The Supplementary Planning Document, the result of a long and extensive community planning and consultation process, concluded with eight Key Themes, but uses such contentious language that serious questions are raised about their credibility, validity, and whether the aims are even definable, achievable or acceptable within the legal framework of the development and planning process. Already these objectives have been challenged as unrealistic and undefinable.

Most of these objectives are too problematic to discuss here but I will comment on one, because it is an extreme example where language is used to promote irrational expectations: the idea of ‘Winchesterness’.

This is an extraordinary concept; can it be defined? I don’t think so.

To imagine it possible to capture and define the character of any city is absurd.

To think it possible to build the future in that image is a fantasy.

The term might reflect over 1000 years of history, of change, the resultant varied individuality of the existing city, architectural styles from medieval to modern, buildings of the stature of the cathedral, small and large houses, educational institutions, the list would be endless and even then would not include the contribution made by people and their way of life. It could only ever be a picturesque snapshot of what is superficially visible now, the aged skin of an indescribably complex sociocultural and economic whole, the city.

If planning applications for real projects are to be determined by their ability to match this undefinable value, on what basis is that judgement made, and by whom? Ultimately such a term of judgement would reduce every scheme to an attempt at mimicry and inevitable superficiality.

The true intention of the term ‘Winchesterness’ is surely to say, the new should look old, the big should look small, the practical appear decorative, put simply, to pretend that nothing has changed.

Nothing derived from such a term could define what is unique, what is the irreducible complexity of Winchester.

The form of the central area has to be determined, but from rational thinking, not romantic or picturesque visions which cannot be made real. Look into the real questions facing cities in the 21st century, why there is a need to build, if there is a need and if so what is it, how is it built, in what form and how funded?

In 2001 the Trust published The Future of Winchester: A Strategic Vision which concluded with the following statement about responsibility:

‘History cannot tell us what to do next; this requires judgment and there is no escaping that responsibility.’

The draft Supplementary Planning Document is seriously flawed by requirements which can never be defined, thus they can never be ‘demonstrated’ or objectively met by a built project. That this is to be enshrined as a requirement of planning approval, even if merely a guide, is beyond belief, beyond reason, and dishonest.

Ray Attfield is an architect and urban designer of repute, who was for some years a member of the Trust Council and took an active part in negotiations with WCC on design and planning matters. Ray now lives in London and France.

Notes on style:

The style of architecture called Modernism grew up in Europe but in England was frequently modified by preferences for, rural over urban, small over large, decorative over plain, softened forms and the use of more natural materials and decoration. Early European Modernism had already absorbed the values of the English Arts and Crafts movement, which with its belief in honest use of natural materials, good craftsmanship, and celebration of fine details, has the strongest claim to define the English way of building.

Similarly, the English interpretation of Classical architecture, always in opposition to the Gothic, was frequently modified by romanticism to the point of being a mix of the two, though what is commonly known as Georgian achieved great heights of ordered refinement in the terraced houses of many towns including Winchester.

Fig 1 - Replacement of a corner site in Upper Street, lslington

(architect Amin Taha) with a building cast from a mould constructed

from photographs of what previously existed. The new windows

relate to the modern arrangement of internal spaces.

Fig 2 - One house in a Georgian terrace, lslington.

An example of simple elegance, scale, classic proportions,

generous large windows and refined detail

- but note, achieved without decoration.

Fig 3 - A project I recently worked on which, via new public courtyard, linked the formality of Sloane Street with the mews behind.

Because the Estate owned the properties they were able to choose and encourage selected retailers to

trade from the re-built mews which is now a thriving street rather than a mere rear access. Architects: Stiff + Trevillion

Fig 4 - A new office and flats, also by Amin Taha, whose internal spatial arrangement

could be said to be ‘baroque’ in its order and absence of corridors, whose sophisticated

enclosing glass envelope is ‘modern’, and whose exterior facade is perhaps ‘Doric’ in its

use of a powerful freestanding colonnade of solid limestone columns and beams, which are the real

supporting structure. A small carved Ionic volute acknowledges the classical origins.