TrustNews Jun 21

The Festival of Britain: 3 May - 30 September 1951

Festival of Britian Advert

Recovery from the ravages of WW2 was slow and painstaking. Plans were discussed in 1943 to stage a large exhibition commemorating the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition. In December 1947 Herbert Morrison announced proposals in the House of Commons for “a national display illustrating the British contribution to civilisation, past, present and future, in the arts, science & technology and industrial design". Clem Atlee decided the title should be the Festival of Britian emphasing a nationaal celebration.

In 1948 Gerald Barry, formerly the editor of the News Chronicle, was appointed Director General of the Festival Advisory Council. Hugh Casson, already a well-known architect, was appointed both Chair of a subsidiary body, the Council for Architecture and a member of the Architecture Planning Sub-Committee. He is remembered locally for the former RBS bank design in the High Street.

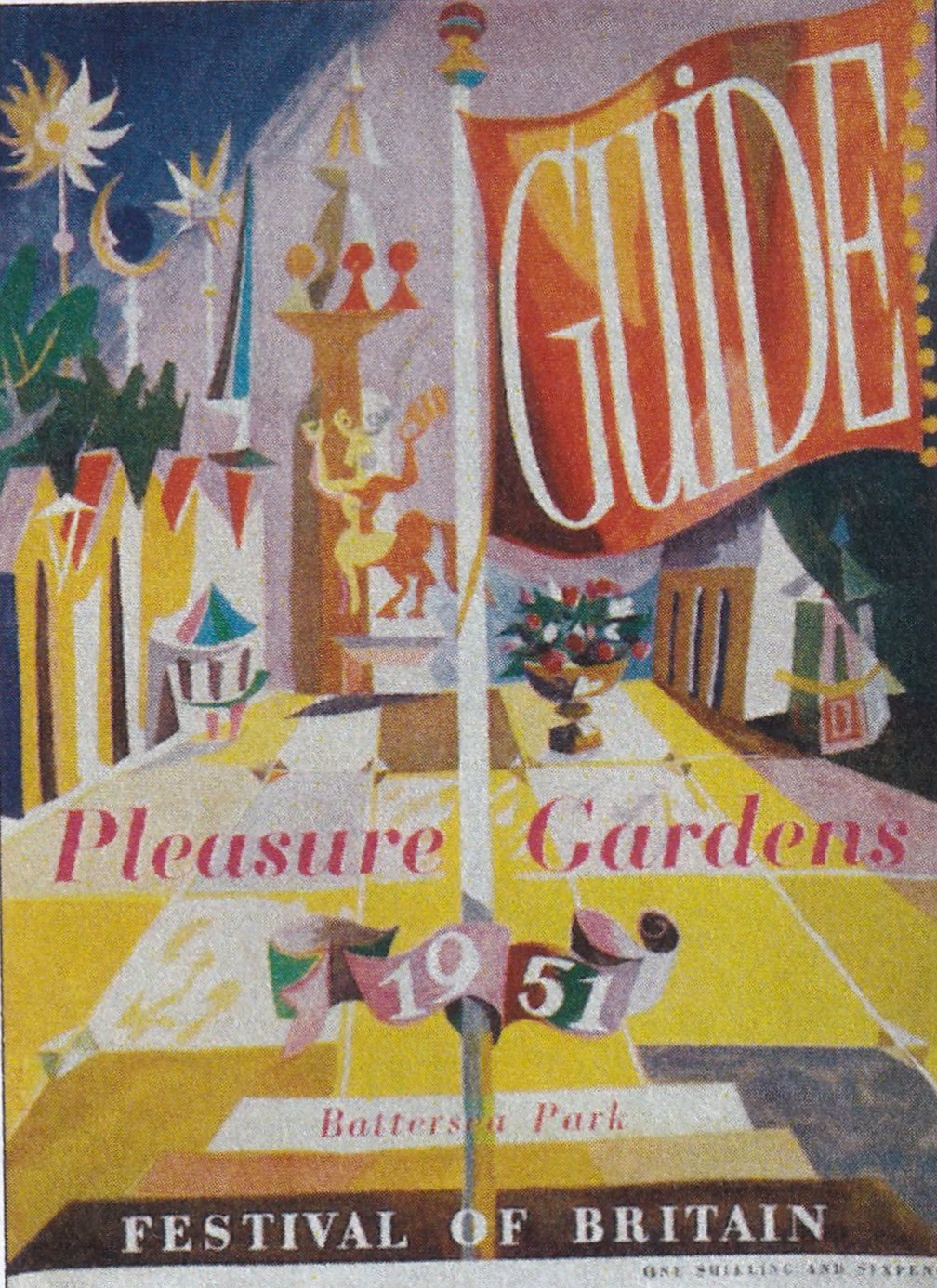

A separate body was established to construct and operate the Festival Pleasure Gardens in Battersea Park.

The construction budget was £11.5m. Final accounts show the actual cost was £10.7m, £800,000 under budget. Revenue was £816,000 less than estimated. It was intended that the various activities would be co-ordinated to have a systematic nationwide impact. Self-taught Abram Games, a highly-recognised War Office poster and graphic designer, won the Festival design competition with his iconic, helmeted head above an elongated four-pointed star sometimes festooned with pennants. One of his maxims was ‘maximum meaning, minimum means.’ He is recognised as one the most formidable and well-known graphic designers of the 20th century. With a strong creative imagination and intense passion for his work, he believed in both the propaganda and promotional power of posters.

Summer 1951 saw more than 2000 Festival events and exhibitions happen across the UK under six main project activity themes, reflecting the theme and content of the main South Bank site, a huge open land reclamation space.

The South Bank Exhibition

Science

Industrial Power

Architecture

Land Travelling Exhibition

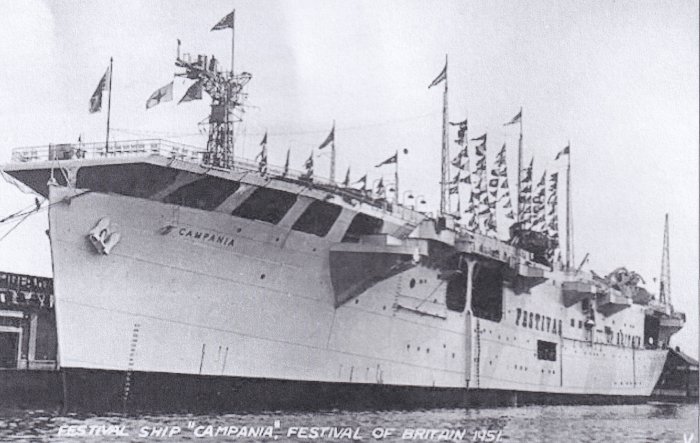

Sea Travelling Exhibition

HMS Campania, a decommissioned WW2 escort aircraft carrier which became the floating Festival exhibition, visited ten UK ports, stopping for two weeks in each including Southampton in May 1951.

Sea Travelling Exhibition

King George Vl formally opened the Festival from the steps of St Paul‘s Cathedral on May 3rd. Over the next five months, there would be local exhibitions, arts festivals, sporting events, simple village celebrations, a living record of the nation at work and play. The objective was to demonstrate the vitality and creativity of British people as expressed in the six themes. It was also to reflect their resilience and determination; to demonstrate their part in peaceful progress and to utilise their skills and talents in the long post-war rebuilding of the country.

During 1950, four London Transport buses drove 4000 miles through Europe and Scandinavia. Designed and configured as travelling exhibitions using models and illustrations, visited by 122,000 people, they publicised and flew the Festival flag. There were eight exhibition sites in London, thirteen arts festivals in major UK towns, nineteen in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Four major cities were visited by a travelling exhibition.

James Gardner, asuccessful industrial designer, created the Pleasure Gardens for enjoyment, pleasure and relaxation, to balance fun with the serious aims of the Festival. Set amongst the trees of Battersea Park, lawns, flowers, courtyards, terraces, fountains and ornamental lakes were created. Accessible by the Thames river bus from the South Bank site, they provided entertainment and refreshment for all ages. There was an open-air amphitheatre for 1250 people, concerts, luxury shopping, a fun fair with rides imported from the USA and a children’s zoo. 400 couples and 700 spectators enjoyed evening dances in the magnificent and spectacular Dance Pavilion. When the gardens were transformed and illuminated at night, an impressively radiant glow appeared creating a peaceful contrast to the blackout Blitz years and existing austerity. Restaurants, cafes and bars offered a variety of refreshments. The very success of the gardens was that their purpose ensured everyone, especially children had fun, embracing the concept and experience of pleasure as part of normal life. The Labour government was keen to widen entertainment choices in order that the public did not become solely dependent on pubs or the cinema. Over 8m people visited the gardens and in 1976, reflecting on the Pleasure Gardens’ 25th anniversary, James Gardner said ‘It did put a moment of dream world into a lot of people's lives.’

Design in the Festival

The major external architectural showcase was the creation and building of the Lansbury Estate in Poplar, East London, heavily bombed in WW2. It was part of the LCC rebuilding London plan, to revive local communities in smaller units, creating neighbourhoods housing between five and eleven thousand people. The 124-acre site was chosen to demonstrate good town planning, contemporary British architecture, quality construction, new design and building techniques. Many buildings were completed by the Festival opening date, but some could be viewed as work progressed, including schools, churches, open spaces, a shopping centre, an old people's home and a market-place. It was the reality of the future being built, a vision to foster positive and hopeful expectations.

The South Bank Festival site was a milestone between past and present, celebrating diversity and creativity, focusing on imaginative regeneration. Architecture was used to re?ect what was already happening outside, exposing tentative blueprints for new towns, chosen to challenge the eye with new ideas. It is not known how many millions of people participated in villages, towns and cities in the UK.

Festival Guide

The surroundings were deliberately unfamiliar, vibrant, innovative, stimulating and experimental. Now part of the re-named South Bank Centre, the iconic Royal Festival Hall designed by Robert Matthew and a team of young LCC architects, opened on the first day of the Festival, remains its greatest and permanent legacy as the first public building built by the LCC after the war. For the 8.5m South Bank visitors at least, including myself as an excited five-year-old, I believe the Festival of Britain succeeded in providing a welcome impetus for the new approach to re-building Britain.

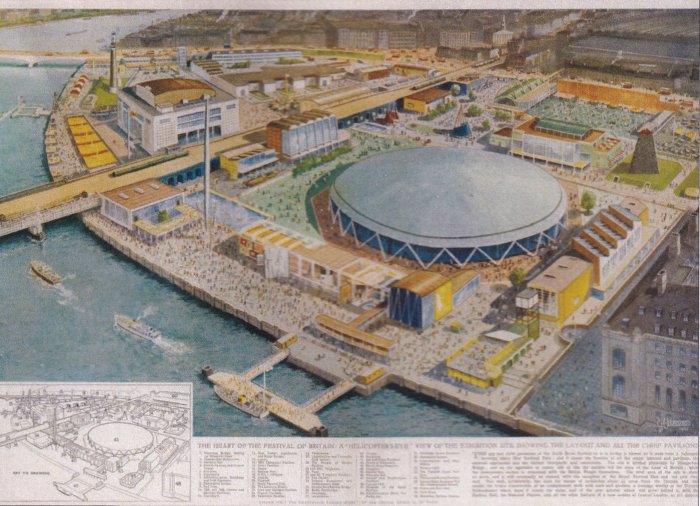

Festival Layout

Peter Rees