A City for People - TrustNews Summer 1986

In March, Police Chief Inspector Michael Finch and City Council Chief Engineer, David Marklew, met a small group of Trust members to discuss a number of traffic-related matters. The Trust requested the meeting, partly to seek remedies for particular problems such as lorry damage and pavement parking, but mainly to explore attitudes and perceptions in regard to the role of cars in an historic city.

Following nearly a decade of debate the Winchester Area Local Plan has finally put paid to the last elements of the destructive road building schemes of the 1960s. The Trust, in generally welcoming the Plan, observed that it was a good parting point and that now was the time to look for ways in which the living, working and shopping environment in the City could be improved. This may appear to be a strange statement, for one might have imagined that the Plan would be a lot more than just a basis for investigation. Yet it is a curious fact that the Plan does not begin with objectives, but with a strategy. The strategy, moreover, is entirely reactive - in other words, where Planners perceive threats or demands upon the City, they propose varying degrees of compromise. This is understandable because, hitherto, the threats to Winchester were pre-eminent and it was essential to secure Conservation as a primary aim. There is, however, nothing beyond this in the new Plan; the Planners say nothing what they would like Winchester to become.

The Trust's Vision

The Trust, in its submission to the Plan Inquiry, attempted to define a long-term objective for the City Centre, by envisaging a milieu in which people dominated the streets, in the way in which old photographs show us they used to do. While the Planners and the Inquiry Inspector were clearly attracted to the idea and believed that in the long term steps could be taken towards it, they could not comprehend that it could have any relevance to planning today.

The tragedy of this for Winchester is that the Planners are currently taking steps, for reasons which have more to do with planning orthodoxy than common sense, which will ensure that the objective of a people-dominated centre will not be attained in our lifetime, if ever. The brief for the Central Car Park development positively seeks to ensure that the motor traffic domination of the central area will be perpetuated indefinitely by constructing a multi-storey car park at its centre. This in spite of a stated objective at the Inquiry "to reduce traffic".

The Trust will try to bring some common sense to the Central Car Park debate in the coming months. There are, however, smaller steps that can be taken towards the objective, aimed more at altering perceptions than at securing significant practical gains. In this we echo the current campaign, "Cities for People" of Friends of the Earth, and take comfort from Mr. Peter Bottomley, Roads and Traffic Minister, who says that "pedestrians have become the Cinderellas of road users" and that "Planners seem to forget that...pedestrians are the most important class of road user."

Attitudes

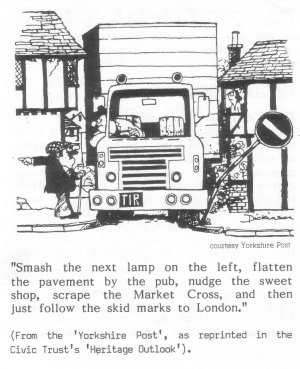

At its meeting with the Police and the City Engineer, the Trust argued that there was a behavioural deterioration amongst motorists in Winchester (as elsewhere), as manifested for example in the rapidly growing habit of driving and parking on pavements. The Trust also argued that local authorities were prepared to spend large sums of money on road schemes, car parks and research into car trip patterns, but next-to-nothing on street crossings, public transport or research into pedestrian movements.

Yet this bias is widely accepted. We suspect that what happens is that a generally liberal tendency prevails (the motorist should be as free as possibe) without any clear perception of the costs of that liberality. The imbalance of perception seems quite general (in fact we see it in ourselves - perceptions change accordingly as we are driving, cycling or walking) and is merely reflected in the attitudes of local authorities and police. Do the police presently feel that enforcing legislation on motorists will be seen as over officious? Do local councils feel that restrictions on motorists will be electorally unacceptable?

And yet it may be that once this imbalance of perception is seriously challenged, the perceptions will begin to change. There was quite a lot of opposition to the High Street pedestrianisation, but if the Precinct were now threatened there would probably be strong objection from the same quarters. And following pedestrianisation of one piece of road, the general acceptance of pedestrian priority on adjoining sections has quietly established itself, reversing the usual roles of cars and people. The Trust suggested at its meeting that all that may be necessary for change, apart from actually asking the questions, is a small commitment of effort on the part of local authorities (to provide, say, more pedestrian crossings) and the police (to clamp down on, for example, pavement parking).

Enforcement

Chief Inspector Finch, while very sympathetic to what the Trust was saying, pointed out that all policing was a question of allocation of resources, and indicated that such matters as pavement parking were very time-consuming and not the highest priority. While the Trust understood this, it made the point that, if there was official resistance to enforcement, the abuse would grow and could have serious consequences for pedestrian safety, and might eventually lead to pedestrians taking their own actions. Chief Inspector Finch said he understood the dangers and would be reporting back on our concerns. We have not yet discerned any improvement in the situation and indeed we have been told that throughout the demolition of the Crown Hotel a car was allowed to occupy sufficient pavement in North Walls to prevent the passage of pram, pushchair or wheelchair - just two hundred yards from the City's Police Station.

Improvements

The City Engineer was clearly very much in favour of the provision of more pedestrian crossings and had specifically sought a pedestrian phase in the lights at the High Street - Jewry Street - Southgate Street junction. Here, as at the Library in Jewry Street, the case for a pedestrian crossing is undeniable, and yet the County Surveyor whose responsibility it is, continues to deny it. It seems that crossings have to be justified by how many people have been killed trying to cross the road without them. With the new guidelines from the Roads and Traffic Minister, the County no longer has this excuse for inaction.

The Pedestrian Precinct has led to a de facto pedestrian domination of some adjoining streets, particularly the eastward extension of the High Street to Middle Brook Street. The Trust and the City Engineer had independently concluded that this pedestrian-dominated street sharing could be formally declared and asserted by subtle alteration of the street scene, particularly in paving details. It was agreed that the integrity of the street, as a street, should be retained, and the City Engineer indicated that at the appropriate point in the normal timetable of road surface and pavement renewal, we can expect to see some welcome changes in these areas.

If the City Engineer's efforts can establish the principle of street-sharing, there might well be pressure to extend it to other central streets. It is all the more a pity that a myopic Planning Department is currently seeking to limit the possibilities by sinking substantial capital investment into the permanent retention of City Centre car parking.