The M3 Inquiry - TrustNews Spring 1988

The latest episode in the 17-year saga of the M3 Motorway came to a close recently with the completion of the resurrected 1985 Inquiry. Those who bemoan the apparently interminable progress of these statutory proceedings and are inclined to blame conservationists for their obstructionism, would do well to ponder where those 17 years have gone.

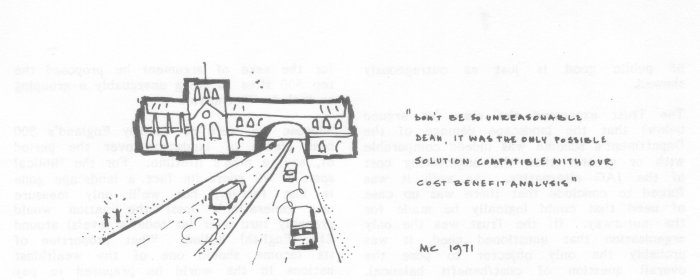

The 1971 Inquiry scarcely merited the term, being a straightforward rubber stamping operation of the kind that was expected in the days before the doors were broken down at Shipley Town Hall in the Aire Valley Inquiry. Conservationists had nothing to do with the 5-year delay that followed, before the "Side-Roads" Inquiry of 1976. Nor could they be held responsible for the adjournments in that Inquiry, or for the 4-year delay before the consultation period started in 1981, or for the 3 years that elapsed from the end of that period until the start of the 1985 Inquiry.

If the process has seemed interminable it is only because the Department of Transport has made it so, sometimes through dilatoriness or incompetence, but more fundamentally because it has never seriously tried to get the scheme right.

At this latest Inquiry the Trust pointed out that, when road builders are blocked by major topographical barriers such as mountains or estuaries, major civil engineering constructions are often used to cross them. These are not always economically justified (e.g. the Humber Bridge), and political decisions are taken to bring them about.

The Trust has argued that there are environmental imperatives as real to any civilised society, as topographical ones. The 17 years of saga of Winchester's M3 testifies to the inescapable fact that there is a barrier at Winchester which will not be surmounted until its existence and scale are acknowledged.

One would naturally suppose that a Public Inquiry into a publicly financed scheme would be set up to determine the balance of public harm and good from the scheme. Yet it is this writer's experience of a number of Inquiries that no serious attempt is ever made to weigh all the costs and benefits in a common scale. This is true even where the Inquiry has not been a rubber stamping exercise (as, for example, the 1976 Inquiry or the Easton Lane Link Road Inquiry).

Certainly there are difficulties in weighing, for example, the benefits of decreased journey times against the costs of ruined landscape. The Leitch Committee in 1978 took a small step in the right direction, but its recommendations are now almost entirely ignored and the Committee's successor body, the Standing Advisory Committee on Trunk Road Assessment (SACTRA) is now seemingly just another part of the rubber stamping machine.

There is no incentive for the Department of Transport to attempt any overall cost/ benefit analysis, because economic factors are easily computable and can be bent in the direction of proving a benefit merely by the arbitrary selection of certain parameters, which nobody is allowed to question.

Environmental factors, on the other hand, are deemed to be impossible to evaluate. This is very convenient for the Department, for it can make the jump from "impossibility of evaluation" to "valueless". With a barrister to make the case, this sophisticated sleight of hand often utterly obscures from Inspectors the equally valid interpretation that what is impossible to evaluate is "invaluable".

The Trust in its evidence, however, set out to demonstrate that certain economic bounds could be put on environmental factors. These would be subjective, it is true, but nonetheless quantifiable for all that. The Trust evidence proposed some thought experiments, with the intention of persuading the Inspector, by the light of his own sensibilities and values, to price what was being lost in the landscape by the Department's scheme.

The reason for doing this is clear. Whatever may be said about resource con¬sumption (the Friends of the Earth case) or traffic effects (as feared by some St. Cross residents), the landscape superiority of the tunnel proposal over the Department's scheme is not to be doubted (even the Department concedes that). The question arises: is the landscape damage of the Department's scheme comparable in cost with the engineering costs of avoiding it?

As far as this writer is aware no-one else at the Inquiry (or at any other Inquiry that he knows of) asked this question in this direct form. By it not being asked the Department can get away wit' plausible, but quite illogical statements:1ov When, for example, a figure of £100 million is mentioned for the cost of a mile of tunnel, it is easy to nod one's head when one is told that such a sum is being diverted from building 30 miles of motorway elsewhere or from urgently-needed by-pass schemes (note the subtle implication that roads are built for environmental reasons and not to increase the profits of road hauliers). Certainly £100 million could buy a lot of good things -the National Trust's Enterprise Neptune, for example, has secured nearly 500 miles of coastline for a £10 million outlay.

Obviously, therefore, it is preposterous to spend £100 million on a mile of motorway, if we weigh it in the balance of general public good. But if the landscape damage of the Department's scheme is of comparable magnitude, the balance of public good is just as outrageously skewed.

The Trust expressed the view (as argued below) that the landscape damage of the Department's scheme was indeed comparable with or greater than the engineering cost of the JAG alternative. As such it was forced to conclude that there was no case of need that could logically be made for the motorway. (If the Trust was the only organisation that questioned need, it was probably the only objector to pose the overall question of cost/benefit balance).

Of course, no-one representing the Trust is likely to be so naive as to suppose that a road will not be built just because it is unjustified. A political decision has been taken to build the road. The Trust case is that that political decision throws out all pretence at economic logic and should, therefore, take on board all the environmental consequences it entails. If a motorway is inevitable, it must be preferable to incur £100 million of construction costs than to incur £200 million, say, of landscape damage.

But how do we calculate landscape damage? The Trust proposed the following thought experiment, which rests on a foundation of, necessarily subjective, priorities. Members may wish to work through the arguments using their own priorities.

In any microcosm of human society we can imagine some priority of needs - food, shelter, security, medicine. Having secured these, we tend to put a lot of effort into making our surroundings lovelier - we decorate our houses and tend our gardens. If these are our priorities as individuals, they ought to he reflected in our priorities as a society at large.

The landscape of Winchester is part of England's great garden and not an insignificant part. It is pointless to compare great landscape of different kinds - Rydal Water, Golden Cap, the Seven Sisters, all precious parts of England. Rut for beauty of its type - chalk hills, chalk streams, a meeting of man and Nature - it would be hard to find much better. Whereabouts in the league of England's landscape areas should Winchester be placed? This writer's view was somewhere within the first 50, for the sake of argument he proposed the top 500 sites as being unarguably a grouping to include Winchester.

Suppose we were to destroy England's 500 best pieces of landscape over the period of, say, a man's lifetime. For the Biblical span of 70 years (in fact a landscape gone is lost forever, hut we'll only measure one generation's loss) the nation would probably turn over (at today's levels) around £15 (English) billion. What proportion of its income should one of the wealthiest nations in the world be prepared to pay in order that it does not lose its 500 finest landscape sites within a generation? 10%, 5%, 1%? £100 million per site represents a mere one third of one per cent of the nation's income in that time.

With arguments such as these it is clearly possible to show that construction costs of rather more than £100 million are not an inordinate price to pay to avoid the irretrievable loss of a major piece of landscape.

Of course there were many other matters at issue in the Inquiry besides landscape and money. most of these the Trust had no competence to tackle, but two matters seem to have concerned some members - accidents and traffic.

The accident record of the existing Win¬chester By-pass appears to be a potent and enduring mythology. There is nothing especially dangerous about the Bar End to Compton section of the A33. A driver who took any other possible route between those two points would be taking a greater risk. An average road of the same length would be riskier. For what the BBC call the "worst road in Britain", what sort of carnage are we all imagining? Recent statistics show no fatalities for the last 2 years for Bar End to Hockley and three serious injuries. For Bar End to Compton there has been one fatality in that time.

The JAG scheme is a better quality road (straighter and more level) than the Department's scheme and may well be safer. But although the accident rate per mile travelled on motorways is lower than that on other roads, there has actually never been any serious study to show whether building motorways reduces accidents. If, for example, the accident rate decreases by 10% but the number of trips increases by 15°A (motorways generate traffic) more people will be killed.

The traffic consequences of the JAG solution have caused some concern in St. Cross, largely on the basis of a Department of Transport traffic model which shows a 15% increase on St. Cross Road between the Department's scheme and the JAG scheme.

Actually the model is rather poor at assigning traffic and makes errors in existing traffic greater than 15% elsewhere on the road network. More importantly, however, the figures that have caused alarm are based on an assumption of an 81% increase in Winchester's radial traffic by the year 2007. This implies an 81% increase in central area car parking. This is totally contrary to the City Council's declared policy of retaining car parking at its present level. Indeed, a stated objective of its Town Plan is to reduce traffic in the centre.

It is not just St. Cross Road, but the whole of Winchester that would be ruined if the Department's absurd predictions were ever realised. The traffic in St. Cross has much more to do with the City Council's parking policy than with the detailed arrangement of motorway junctions.

Of more direct concern to St. Cross residents should be the City's allocation of parking on the Peninsula Barracks site. The City is also supposed to be investigating Park and Ride schemes for winchester. Since one of the prime potential locations for a Park and Ride site must be Bushfield Camp, residents of St. Cross stand to be beneficiaries of such schemes and might do well to lobby accordingly.