The Mizmaze Puzzle - TrustNews August 1990

Some thoughts on the origin of the maze on St. Catherine's Hill

One of the most famous mazes, of which St. Catherine's is an example, is laid out in stone on the floor of Chartres Cathedral (see the illustration on the cover). Not many visitors are aware that they have crossed a maze when they walk up the centre of the magnificent medieval aisle because the circle is about 40 feet in diameter, stretching from one side of the nave to the other, and mostly concealed by chairs.

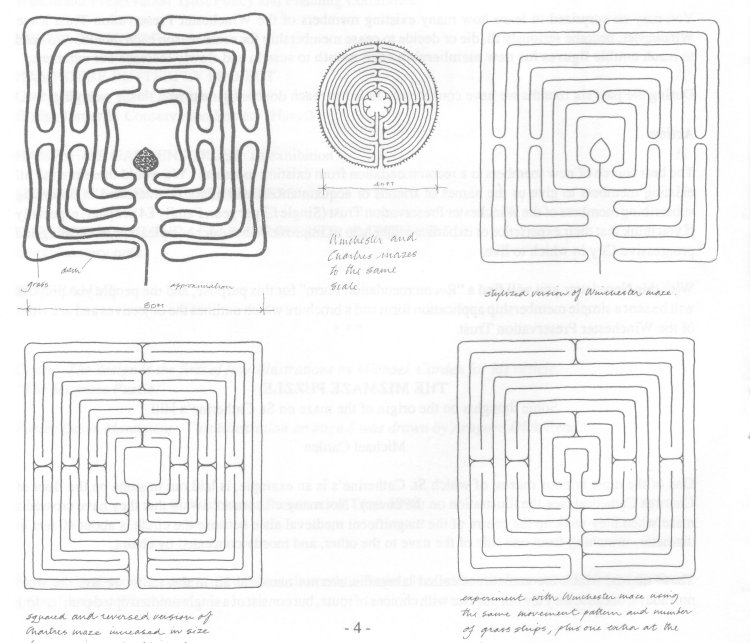

These mazes, which are sometimes called labrynths, are not mazes at all in the sense we use the word nowadays, because they are not puzzles with choices of route, but consist of a single uninterrupted path leading inevitably from the entrance to the centre. I believe that they are all of the same basic design too, whether the simple "mizmaze" cut in the turf of St. Catherine's Hill above Winchester, or the great maze at Chartres, or the oldest known version scratched onto the stone wall of an 11 th Century chapel in Italy.

This very early example has a Latin inscription describing it as the labrynth designed by Daedalus for King Minos of Crete. I do not know how this affects other people but it makes the hairs stand up on the back of my neck to think that the pattern I shuffled around in the rough grass with my children could be the very same which was known to King Minos thousands of years ago in a world I had looked upon as legend. The consistent pattern is not the only link either, for it seems that until it was taken for munitions during the Napoleonic wars there was a bronze plate at the centre of the Chartres maze depicting a minotaur!

My few examples are a fraction of the number which once existed, and there may be many more than I know of around today. I have heard that Amiens Cathedral had a similar paved maze in the 18th Century (removed because it encouraged children to play in the cathedral, I believe), and I am told that at Braemar in the New Forest there is another turf maze; these were once, it seems, scattered widely throughout the countryside of England.

What were they all for? Maybe someone has researched and explained them in detail, but I can only pass on one or two certainties and some sketchy conjecture. Obviously the mazes had religious significance, Christian at least in the cathedrals and probably a mixture of christian and pre-christian in the countryside.

Winchester and Chartres Mazes

The pre-christian symbolism is probably to do with the sun and the moon as there appear to be links with the calendar in the layout of the mazes, as there are in stone circles and in ancient games like hopscotch. The christian purpose may have been to create a ritual pilgrimage for those who could not travel to the holy land, so that they might progress on their knees and in prayer (each corner serving like a bead in a rosary), until they reached Jerusalem - as the centre was sometimes called. One is reminded of Sir James Jeans' remark that to travel hopefully is more important than to arrive. Some say that the return journey was also important, culminating in the blaze of light from the rose window at Chartres, which it is claimed has a mathematical relationship with the maze.

Such theories can seem conclusive, with mathematical measurement turning into proof. It is confusing, then, to learn that there is historical evidence of the Chartres maze being used for religious games rather than pilgrimages. Apparently the king and his court would sit as spectators while the clergy sang and danced around the maze, lobbing some object from one to another in festive worship. One can certainly imagine something more along these lines on St. Catherine's Hill than pious Wintonians painstakingly shuffling around the damp turf on their knees.

Which reminds me that the Winchester maze is said to have become distorted because, when it was first recut by restorers, the pattern was misunderstood so that the bare earth has become the route, where it should form the lines of division between the encircling turf paths. And this is where there is now a genuine puzzle: what should be the pattern of the maze? There are 11 circular paths at Chartres but only 8 strips of turf at Winchester; have 3 been lost? Certainly the centre seems over large and an outer ring could easily have been lost. So perhaps there should be 2 more in the centre and 1 outside? Or was it always an 8 ring version? Perhaps careful archaeology would give the answer.

There is then the question of the loops. Is there a missing boundary line in each loop? This would make 12 paths on the south side but only 10 on all the others, yet the layout appears symmetrical on both axes.

I remain mystified and hope that someone will see a clue which I have missed. All you need is a piece of tracing paper and a great deal of patience!.