Of Mynstres and Mills - TrustNews Summer 1994

Water was essential to the early religious communities, not only for the obvious reasons of supply and drainage, but also as a source of power for milling. Did the Saxon community and its successor at St Cross have a mill within its precincts?

John Keevil, who was actively associated with the milling trade until 1960, and for whom archaeology has been a lifelong interest, sets the scene and explains his theories about St Cross.

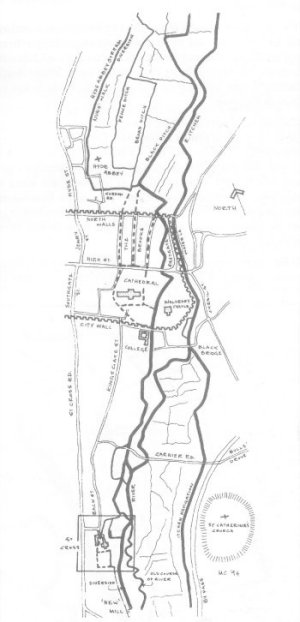

The 1083 Domesday Survey of Chilcomb, an area which extended across the Itchen valley from the south wall of the city to the boundaries of Twyford, mentions nine churches including St Catherine's-on-the-Hill and the White Monastery. Milner in his history of Winchester, writing in the 1790s, mentions that soon after our island was converted to Christianity, a monastery was erected at Sparkford on the site of St Cross. This may be no more than speculation on his part, but the evangelising monks did set up 'kieves' (their local headquarters) at strategic points around the country and Sparkford would have been in a good position where, presumably, there was a ford across the River Itchen and its boggy margins.

There is some evidence that like many communities in the south of England, the monastery here was attacked and laid waste by the Danes during the ninth century, perhaps then struggling on in a depleted form until adopted by Bishop Henry de Blois for his new foundation of St Cross Hospital at the beginning of the 12th century. When King Alfred died in 901, the two great communities of New Mynstre and Nunna Mynstre were founded in the City under the terms of his will, and it is possible that the Sparkford Monastery received some restoration at this time of revival.

It is significant that the church at St Cross, unlike its near contemporary the Cathedral, has the same orientation as these Saxon mynstres, suggesting earlier origins than the present Norman building. The Sacristy on the end of the south transept is believed to be Saxon work and, together with the traces of a cloister between it and the chancel of the present church, provides a clue to the original layout of the domestic buildings, which would have been served by the existing water course designed to run close by the cloister before turning south to join the river further down stream. The importance of mills to religious as well as to secular communities can be judged by the early history of the city mynstres. Nunna Mynstre on the site of the Abbey Gardens had its own stream, water rights and mill within its own precinct from the time of its foundation. These water rights were jealously guarded because, without water power, corn would need to be ground daily with a hand quern - a most laborious business.

When founded, New Mynstre (on a site north of Old Mynstre in the cathedral grounds) had neither water nor mill within its immediate precincts, so it had to acquire milling facilities by other means. John Crook in his excellent article "Winchester Cleansing Streams"* describes how in about 970 Bishop Aethelwold brought water into the precincts of both New and Old Mynstres by diversions from the Black Ditch through the area of the Brooks.

The Headbourne Worthy stream of the river originally fed into the Black Ditch near the village, but was diverted to impound water for a mill at Hyde (near the white bridge in Gordon Road). Mill pounds were necessary to achieve a sufficient head of water to drive a mill wheel when the strength of the diverted stream on its own would not provide sufficient power. Some worked on a continuous basis and others by storing up water over a period of time and releasing it to drive the mill at intervals.

In 1110 the New Mynstre was moved to Hyde adjoining this mill and became Hyde Abbey. An interesting question then arises as to whether the Headbourne diversion was done as precursor of the mynstre's move, since both streams were part of the water rights of the Abbess of Nunna Mynstre, who claimed damages from the Abbot for diversion of her water in 973. The following is an extract about the adjustment made by King Edgar, given to me by the late Sidney Ward-Evans, Hon Archaeologist to the City in 1930, which may refer to this incident:

"In the 10th century Aethelgar, Abbot of New Mynstre, with the consent of King and Bishop, assigned for peace and concord to Eadgyfu, Abbess of Nunna Mynstre, the King's daughter, the same mill which the Bishop gave and another with the Borough instead of the water course which he had diverted, formerly belonging to the Nunnery".

In any event, the nuns appear to have patrolled the banks of the Headbourne Worthy diversion to the extent that it is still known as Nuns' walk to this day!

The importance of mills is illustrated by these records, and by the fact that there was much other water engineering carried out at this time. Domesday mentions four mills in the Chilcomb area; I would suggest one at Blackbridge, two at Gamier Road, and the fourth, perhaps the mill at Sparkford which was to become St Cross.

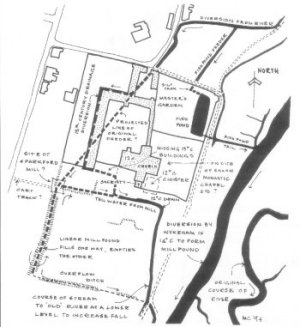

Plan showing projected line of stream through the Hospital

The stream which taps off the Black Ditch at Garnier Road to supply St Cross is similar in size to the Hyde Abbey diversion and could very easily have had the same purpose of feeding a pound. The stream was channelled through the Meadows and can now be seen in the area north of St Cross from where it runs on underground across the outer court of the Hospital on the same diagonal line, until it meets the 15th century buildings on the inner court and is diverted around them to form their drainage system.

If the stream's original line is projected across the later inner court, as shown on the plan, it meets the north west corner of the excavations which can still be seen in the park to the south of the present Hospital buildings. If the banks of the stream were slightly raised using the soil from its trench, it would then have been about nine feet above the point at which the tail stream rejoins the river. This fall would have been sufficient to drive a mill from water impounded at the higher level.

There are excavations and embankments at this point which indicate the possibility of a linear pound running due south to meet a small ditch which also runs back to the river and could have been an overflow channel from the pound. And the present white gate onto the main road with traces of a track (now extended beyond the pound), might even be the original entrance and lane for the corn carts.

Christopher Currie has recently written a fascinating article in the journal of the Hampshire Gardens Trust outlining his investigations and conclusion that these previously mysterious earthworks are the remains of a large rectangular medieval moated garden, a useful arrangement in the days of freely wandering deer and vagabonds. Our theories are not, however, mutually exclusive, as the necessary water engineering for the mill would have created much of the enclosure needed for a later moated garden.

It can also be seen from the plan that the water feed to the fish pond in the Master's Garden is parallel to the water course running through the outer court, and that the line of the outlet from the fish pond is parallel to the remains of what would have been the tail water stream from the mill that also provided the drain from the domestic buildings adjoining the present Sacristy. This all implies a contemporary master plan for the water engineering which, in a monastery of that time, would almost certainly have included a mill.

The main course of the river in Saxon times was to the east of the present line, but it too was later diverted to form a mill pound, and the following extract from the records (13 Richard II 1392. William of Wykeham, Bishop. John de Campden Master) records how this came about.

"Stagna et dua excluse molendinum cum sagitta et unum molendinum the tribus videlicet ad orientatem partem dictorum molendinorum de novo facta fuerent".

I have given it in the original Latin in case anyone wishes to improve on my translation, which is:

"They have newly made a mill pound and two mill hatches with sluices and one mill away from the community clearly to the east away from the part of the mills' control".

This "newly made mill" must refer to the present St Cross Mill further down stream, and one can still see its embanked mill pound, the two sets of hatches and their sluices, and the mill buildings themselves which have, of course, been rebuilt many times over the intervening years. The last line of the extract emphasises that the new mill was remote from the control of an existing earlier mill, which supports the case for there having been a Saxon mill at Sparkford and St Cross.

Perhaps the old mill had become inadequate, or perhaps Bishop Wykeham even foresaw the need to enlarge the accommodation at St Cross, which would require the destruction of the little Saxon mill with its headwater embankments, and cleared the way for the great reconstruction that his successor Cardinal Beaufort carried out some 50 years or so later.