....An Eye on the City - TrustNews Summer 1996

Ways of seeing by Ray Attfield

Ray Attfield is an architect, with a particular interest in public places and cities, who has recently come to live in Winchester, and is now a member of the Trust.

The first time I noticed that the idea of Winchester had become encapsulated as an image in my mind was one summer evening, returning home along the M3.

Just before junction 9, where a rise in the road briefly revealed a distant view of Winchester, the late sun was catching the North face of the cathedral as it lay stretched across the valley, white against the buildings of the city. Now, when I think of Winchester, this is the image which flashes up, quite independent of the experience which first registered it. It was this realization that made me wonder how just a glimpse, out of the corner of an eye, could make such a powerful impression. I know the eye takes in a prodigious quantity of information in a split second but looking again, with a critical eye, at the same view it is clear that it is only possible to see very little. Most of the image conjured up is derived from knowledge and experience gained from being in the city, from reading about its history and, perhaps most importantly, from what Winchester has come to mean to me. The image is like a picture, an instamatic photo made up from a mix of reality, imagination, and myth triggered by that flash of light through the car windscreen.

Winchester, the buildings and the people, are a physical reality, but my picture is an ideal, a landscape composed and framed in my mind, which on entering the city, dissolves to be replaced by experiences more than views. Many cities present themselves in this way, nestling in valleys and visible from a distance, but when actually in the streets few live up to the expectation formed by the first impression. I think Winchester does because the experience, the contact with the city, has quality.

Views will always be misleading, not only by revealing very little but by their association with the romantic idea of cities in their landscape, with 'the view' as in a watercolour painting or a picture postcard. What I see from the distance is what I would like to see, what would be better framed as a picture, where unacceptable realities are often represented as desirable images. In a view this is made possible by literally distancing, separating, the viewer from the situation, removing any obligation or need for involvement, denying even the possibility of participation, freezing out the life. Being concerned with how things look, even at close range, has this effect of distancing the eye from the reality of the object. The eye is conditioned to seeing in the form of pictures giving preference, and therefore acceptance, to things which fit, and rejecting that which doesn't.

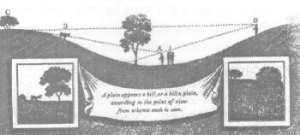

Ha - Ha Figure 1

What clearly doesn't fit into this prescribed picture is anything which blocks the view or distracts from the particular qualities and characteristics required by the composition. Foreground and middle distance are particularly crucial since this is effectively the stage on which life is enacted, but if interest is focussed on the scenery then the people will be in the way. Watch someone take a photo of a scene or a building, waiting for a clear view, for the stage to be cleared. The builders of C18 country houses demolished whole villages and invisibly defined boundaries with the ha-ha (fig 1) in order to compose a view which conformed to an idealised picture of nature as seen from the view point of the house. This single point of view, literally, controlled the whole field of vision as far as the eye could see. In this case the illusion of control over infinity was supported by a great deal of real power over land and people. In choosing to look at something without accepting its context we are imitating the view taken by the C 18 landowner, but without the power to change the intervening situation. Making a picture gives us an illusion of control over what we would like to see, a way of making an ideal composition.

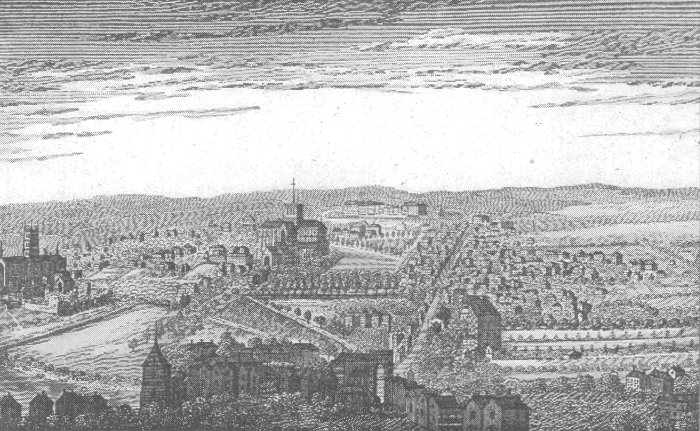

18th Century view from St Giles Hill Figure 2

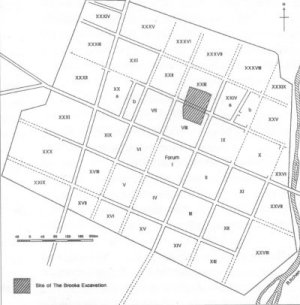

Site of Brooks Excavation Figure 3

The C18 view from St Giles Hill (fig 2), like any from an elevated position, enables an overview of the city as if from on high. There below are the streets and buildings, the monuments and features, laid out like a model toytown. The view point is above the hurly burly and the noise, and free from the pressures of life. The whole picture can be taken in and the relationship of one place to another easily understood. Except for an aerial view it is the nearest to being seen as a plan. The Roman plan of Winchester (fig 3) could only have come about by using a conceptual framework which allowed humans to look at the world from the same position as the gods, from above, and thus define an order which for the most part ignored the physical realities of the geography. The abstract character of the heavenly view, with its resultant flattening of surface features, was in complete contrast to the picturesque aesthetic where the level of the human eye in relation to the ground was an essential reference for the definition of beauty in nature.

Edmund Burke, writing in the mid C18, developed the idea that nature, together with architecture, could be judged in the same way as paintings, and depended above all else on sensory experience gained through the eye, "...beauty demands no assistance from our reasoning;". Burke explained beauty as an almost exclusively visual experience, quite separate from qualities such as proportion or convenience, requir¬ing only a cultured eye with good taste. At the beginning of the C19, Humphrey Repton the landscape gardener, wrote a treatise explaining how beauty could be separated from the ordinary world. His 'eye' (fig 4) sets out the 'field of vision' in relation to the ground and the extremities of the frame, and gives an example of the correct manner in which to view a 'landscape' and distinguish it from a mere 'field' (fig 5). The caption reads, with my comments in brackets; "A plain appears a hill, (image on left with tree silhouetted to form a balanced and beautiful composition) or a hill a plain (image on right without sky; bad composition or ordinary field) according to the point of view from whence each is seen."

Figure 4

Figure 5

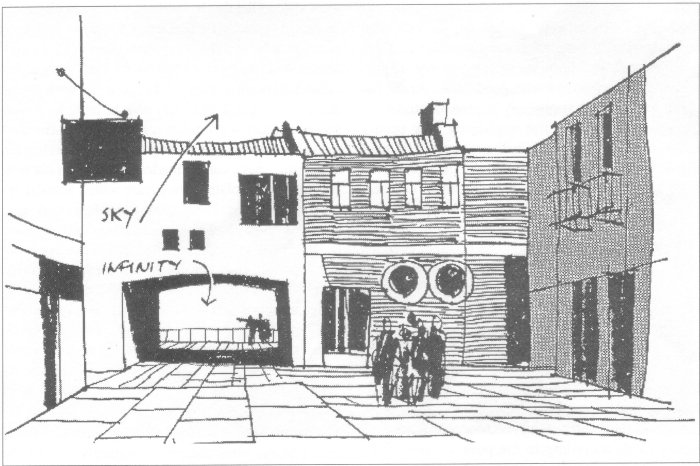

Just after the 1939-1945 war, the Architectural Review published a long running series of articles on civic design by Gordon Cullen which culminated in the book called `Townscape' "...the art of giving visual coherence...to the jumble of buildings, streets and places that make up the urban environment" and claimed for the first time to "...explore the fact that certain visual effects in the grouping of buildings were based on quite definable,...aesthetic principles." The examples in the book are presented as framed views, or sequences of views (fig 6) as in a cinematic story board and judged according to the resultant compositional effect. Townscape, in its approach, is little different from Repton's prescriptive method but it does allow the inclusion of some, selected, everyday objects - and people. Interestingly `townscape' has entered the language as the word used to describe the desirable qualities in a city, even though its meaning still carries the same weighted preference for beauty as perceived through the visual senses and the same exclusion of values only perceived through reason. The concern with 'what places should look like' may now be more inclusive, but essentially it promotes a myth derived from attractive drawings and photographs. The assumption is that the image can be made a reality, can come to life, but the desolate town square which actually results from this approach is all too familiar. Beauty as defined by Burke, even in the modified form adopted by townscape, is still placed above and separate from all else, and by giving preference to aspects which exclude much of everyday life, and by being in opposition to utility, becomes a questionable basis for judging the design of cities. The qualities of beauty, Burke says, are in being small, smooth, varied but not angular, delicate without appearing strong, and in submissiveness; "we submit to what we admire, but we love what submits to us."

The perspective drawing, still the preferred form of architectural presentation, unwittingly carries the stigma of the picturesque view. Such views do not choose to include the complexities of the everyday context, the people, traffic, the closeness or distance of the surroundings, or the sounds. In spite of the potential of computer generated movement through space, the preference is still for watercolour and soft pencil, because it gains credence through association with, and frequently being, a picture hung in a gallery.

Figure 7

There is another eye, another way of seeing, represented here by a drawing from Robert Fludd's 'Ars Memoriae' of 1619. It is called "Oculus Imaginationis" (fig 7) and is concerned not with what we see but with the mind's eye, what is known and imagined, the encyclopaedia of memory and giving a significant place to all knowledge, experience and ideas. I am not proposing it as a method for today, but as a symbol of other ways of 'seeing', which, importantly, include what we know, what we remember, and even what we imagine, as well as what our eyes tell us.

If I were to suggest an approach to looking at cities, it would have to depend more on the use of language, descriptive and poetic, than on a visual image. Memory, imagination, knowledge and the use of reason are not best described in pictures, except perhaps pictures of the mind, as are conjured up by this vivid scene from 'Invisible Cities' by Italo Calvino, (1974). The author uses the imagined descriptions by Marco Polo to Kublai Khan, of his journeys to the wondrous cities of his explorations. The Khan sees his world as infinite. The more Marco Polo sees, the smaller his world seems.

“ ‘Happy the man who has Phyllis before his eyes each day and who never ceases seeing the things it contains,' you cry, with regret at having to leave the city when you can barely graze it with your glance.

But it so happens that, instead, you must stay in Phyllis and spend the rest of your days there. Soon the city fades before your eyes, the rose windows are expunged, the statues on the corbels, the domes. Like all of Phyllis's inhabitants, you follow zigzag lines from one street to another, you distinguish the patches of sunlight from the patches of shade, a door here, a stairway there, a bench where you can put down your basket, a hole where your foot stumbles if you are not careful. All the rest of the city is invisible... Our footsteps follow not what is outside the eyes, but what is within, buried, erased. If, of two arcades, one continues to seem more joyous, it is because thirty years ago a girl went by there, with broad embroidered sleeves, or else it is only because that arcade catches the light at a certain hour, like that other arcade, you cannot recall where. Millions of eyes look up at windows, bridges, capers, and they might be scanning a blank page. Many are the cities like Phyllis, which elude the gaze of all, except the man who catches them by surprise."

For Marco Polo, Phyllis is Venice, 'that decaying heap of incomparable splendour', as are all the cities he describes. Such a description could be about Winchester, full of memories, surprises, and unseen splendours, which elude the eye.

Figure 6

In a future issue of the Newsletter, I hope to explore one particular corner of Winchester; to look more closely at the drama on the stage created by the scene, to remove the mask of the facades which are presented to us, and see what treasures are hidden from view.

Acknowledgements:

I am indebted to Judy Attfield for advice and editing, to Graham Scobie of Winchester Museums Service for information and permission to reproduce the Roman plan of Winchester, and to 'Printed Page' of Bridge Street for the loan and permission to reproduce the C18 view of Winchester.