....An Eye on the City - TrustNews Spring 1996

Following his article "... An Eye on the City" in the Summer 1995 Newsletter, Ray Attfield continues his exploration of Ways of Seeing by directing our attention to the ground beneath our feet.

BENEATH OUR FEET

Some years ago I visited Cologne for the first time and was driving into the centre via a side road when, much to my confusion, the paving suddenly changed from asphalt to a chequerboard pattern of polished black and white marble. It was like one of those dreams where you suddenly find yourself somewhere you shouldn't be. Yet the people around me were quite unconcerned at my presence. As I crept forward looking for an escape, tyres squeaking on the shiny surface, I realised that here the car had no rights except those allowed by the crowd. Though I had driven quite legally into a main shopping street, the paving surface alone had dramatically reversed the priorities and changed the space from road to street.

Perhaps because of that occasion, I realise what a different experiČence it is to walk in the centre of Winchester High Street rather than being squeezed at the edge, between window and traffic. But in Winchester the wide pavement provides a quite different experiČence to that of Cologne where, like most European cities, the streets have a more urban character. In England, because the preferred ideal is a village not a city, 'landscape' is an essential ingredient in the design of urban space, and the ultimate measure of its quality.

The comic scene by Sebastiano Serlio c.1537

Theatre set depicting a domestic city street

The High Street was immeasurably improved by the changes made in 1976. Removing the right of free passage for vehicles allowed all sign of the roadway to be eradicated and the ground repaved with a material to suit the new purpose - practical but also acknowledging the different value which the space had acquired. Now people behave differently, they spread out into the space and stop without fear of obstructing the flow. Groups form and chat. Buskers, even whole brass bands play to a gathering crowd in the space which has become a place rather than a route. But the removal of traffic also deprives the street of the dynamic which historically was the underlying force behind the apparently random arrangement of buildings and space. Had the High Street been intentionally designed as a place it would have had formal characteristics and an ordered arrangement of its elements, one of them being the paving. The existing paving, an imitation riven York stone, has worked well for twenty years and practicalities apart, is accepted because its rustic surface and random pattern have traditional connotations which fit into the picture most people have of life the High Street. It is also true that real stone would have been preferred because that would be even closer to the absolute value - nature. What the chosen paving doesn't resolve however is the changed character of the space and the absence of both the dynamic practicality of its origin and the formality deserved by its new status as a public place.

Looking at the map of Winchester, it is noticeable that within the line of the Roman city, the spaces of the organising grid are called streets whereas outside they are called roads. On the ground the difference between road and street may not now be very obvious because the medieval development of the City did not include the concept of street. Roads, or carriageways, which for convenience followed the line of the Roman streets, resulted in a space determined pragmatically, by convenience of access and throughway. Buildings were positioned along the roadside and, over time, gradually encroached into, and eventually over the carriageway. The Pentice, for example was probably formed in this way. Space in the city intended for the gathering of people was rarely planned intentionally. The informal, irregular character which is the familiar picture postcard scene was created by the very basic and disordered forces of the roadway and the traffic it carried.

Characteristically roads go from place to place, are essentially practical and efficient, and not much concerned with what happens along the way. They need strict rules to control and effect their purpose. Kerbs to 'curb' the wheels of vehicles, complex junctions, and smooth surfaces marked with lines and clear instructions to achieve maximum flow. The result is that people need to be protected or kept separate from roads or their effectiveness has to be drastically compromised.

The meaning of street is derived from the Latin strata, literally meaning stones spread across the ground. Streets are first and foremost public places, made by and in relation to buildings, like rooms, varying in importance according to where they are in the city and the importance of the buildings which front onto them. Vehicles have a more ambiguous involvement. They are accepted, and may even temporarily overwhelm but do not determine the purpose or character of the place. When traffic rights are removed the street can recover its humanity without the need for reconstruction.

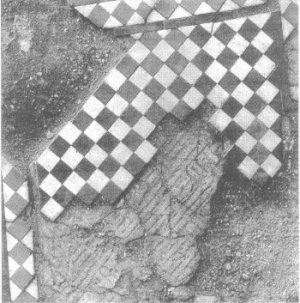

Study for the broken path - a relief painting by the Boyle family

The difference between road and street is more to do with what type of space was intended and how that concept was shaped and manifested. The fact that cars are allowed into the Cathedral Close does not make the Close into a road; too many other factors are involved for a space to change from one meaning to another merely by altering one aspect of its use. To change a road to a street is not so impossible but it does require an understanding of the difference between the two.

Far more problematic are recent proposals for the High Street up to Westgate because improvements to the road must at the same time make it less effective. The aim is that through the application of aesthetic criteria, the visual characteristics identified with roads will be replaced by those associated with the imagery of places of character. In this way it is hoped the road will be disguised. Paving materials which reproduce the appearance of being, natural, old, and weathered, would be chosen for their connotations with landscape. For the same reason the preference would be for a variety of materials, curved lines rather than straight, and elaboration rather than simplicity. These materials, shapes and preferences would then be used to express where one can or cannot drive or park a car, ride a cycle, walk or cross the road including, of course, markings required by law. Textures to help the visually handicapped, ramps to carry cars, different ramps for those in wheelchairs, plus an array of signs and street furniture, add up to the formidable list of elements which have to be clearly visible yet absorbed within the disguise of the whole visual landscape. The result is often complicated and contradictory, confusing necessary instructions with aesthetic messages, and all in an attempt to negate the reality of the road rather than create urban qualities more able to accommodate the complex realities.

The materials used in urban improvement schemes are mainly drawn from one catalogue which may go some way to explain the rapid growth of an almost universal type of town centre improvement which has acquired the title of 'Heritage Style'.

The conflicting and contradictory interests which surround the relationship of vehicles to town and city centres is fundamentally important to the future quality of urban life. It is not a new problem and will not be improved let alone solved by a cosmetic dusting of cobbles and bollards.