....An Eye on the City - TrustNews Spring 1997

Arrival at a city gives the all important first impression. Ray Attfield continues his series "Ways of Seeing", with an exploration of different ways of making an entrance.

GATEWAY TO THE CITY

This essay, prompted by the proposal to erect notional 'gates' on roads coming into the city, takes the view that where the City begins is not something to be marked out as an elaborate traffic sign but, if at all, it has to be understood as an event and a place of considerable civic significance. It begs the question, as to whether at the end of the 20th Century, it is relevant to mark entry into the city, and if so where and how.

"I should begin by describing the entrance to the city. You, no doubt, imagine seeing a girdle of walls rising from the dusty plain as you slowly approach the gate. Until you have reached it you are outside it; its compact thickness surrounds you; carved in its stone there is a pattern that will be revealed to you if you follow its jagged outline."1

Winchester's Westgate typifies the idea of a city gate. A defensive medieval structure, an arched way into the city and to all the different conditions that entering in implies; being in and safe, arriving home, different laws, conventions, privileges and rights, different manners even different dress, different taxes and costs of living. Even today the city is a world apart from the country.

This is not a Gantry. Ce ne pas une Porte

Westgate is however no longer the point at which change occurs. The city has spread, broken out of the confines of its defined boundary, grown out of its skin. The `urbs' becomes 'sub-urbs', something less than civitas, where less important and less acceptable activities are accommodated, where land is cheaper, more available and less constrained by planning controls. The boundary may be blurred but is still defended, though now it is against development. Entering by car, the city takes shape only gradually:

"..it is not clear to you whether you are in the city's midst or still outside it. Every now and then a cluster of constructions, seems to indicate that from there the city's texture will thicken. But you continue and find instead other vague spaces...."2

The concept of city is an expression of common aspirations, which are formalised and made particular by the place, thus Winchester is unique through its geography and history, but in common with other cities aims for wholeness and harmony. Plato's idea of a city required the site to be circled by a wall and the space within divided into plots, each plot then subdivided to give every citizen a share of the superior central area and the inferior periphery.

The founding of a new Roman city involved geometrically setting out the symbolic centre, and ceremonially defining the line of the boundary wall with a plough furrow. When each of the four cardinal points was reached, the plough was lifted and carried across what would become the principle gateways. The Latin portare, to carry, in this case the plough, gives us the words port and portal. In French porte is the gateway to the city, even on the Paris Peripherique, and in English a port is the entrance into the country and a haven from the wild seas.

The Anglo Saxon gate, more commonly used in England defines the practical role of the gateway as a means of control or defence but also includes the spaces each side, used for gatherings of people engaged in the important events of entering or leaving a city. The different words reveal two distinct histories of the idea of entrance: gate describing a practical construction, sometimes decorated with the emblems and insignia of authority, and, porte, also practical, but intentionally given symbolic value at the moment of its creation. A gateway intentionally instilled with meanings beyond the mere practical is made significant, and is thus more appropriate as a city entrance. The use of geometry, for example, establishes a relationship with the earth and the sky, thereby claiming fundamental values about time and space, which are beyond individual opinion. In ancient Rome, special protection was given by Janus who was primarily the god of public gateways, Jani, through which roads passed. With his two faces he could oversee both arrivals and departures, and thus the new beginnings [January for example] of all human initiatives and enterprises. The Roman idea imbued arrival at the city gate with hope, expectation and peace after the uncertainties of travel through the wild world outside. Perhaps the return home from London, after a hard day at the office, might invoke similar feelings of occasion if the gates of Winchester existed.

The walls of most European cities were demolished during the C19 to accommodate massive expansions of population and industry. Most frequently the space created was replaced with ring roads which, as with the city walls before, became the new means of peripheral communication and also, by default, a no-mans-land often more throttling than the walls they replaced. Removing the boundary wall cleared away the implied restrictions of an historic relic in exchange for the implied benefits of unrestricted movement, and with it went the distinction between city proper and the suburban sprawl which had accumulated 'without the walls'. Improvements to transport systems and living accommodation were necessary, and an essential part of the open and more egalitarian cities of the C20. Plans of the modern city look deceivingly similar to the radial cites of ancient Rome, [2] however the modern city is based on the uninterrupted flow of fast moving traffic. Recent realisation that this is a problem contradicting almost every aspect of what gives a city quality and significance, has produced a Canute like response, to hold back the tide, but not unfortunately to question the basic assumption that traffic rules.

And this is not OK.

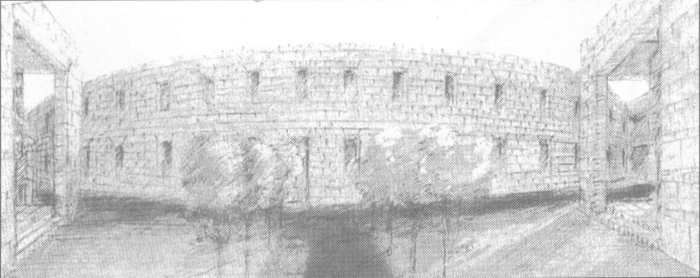

Multiple layers of cars within what could be a majestic wall - a city wall as car park

Winchester, mainly through the efforts of the founding members of the Trust, narrowly avoided the worst aspects of a ring road or road widening schemes, but it has its share of no-mans-land roads, and still it is the ideology of traffic efficiency, developed in the post war era, which determines the physical shape of our streets. There has been no serious revision of this approach. The current policy of making traffic adapt to the City does create a rare opportunity to implement a positive alternative, but the omens are not good. The Park and Ride scheme offers enormous potential for the car parks to be termini or points of arrival but we are offered only a land-wasting field of cars in what will inevitably develop into a ring around the city. Is this to be the image of arrival ?

Contender for the greatest insult to the idea of a city gateway is the suggestion that the start of the 30 mph speed limit should be honoured as an entrance to the City. These anonymous locations have no significance except to inform drivers of one aspect of traffic law. They can reasonably be compared to signals on a railway but not to gateways (Fig I) . To mark them as important is to celebrate a mere change of speed, which is probably ignored, and to degrade the whole idea of arrival in Winchester.

My references to the Roman idea of the city may seem distant and romantic but I suggest it has much to offer as a way of thinking about what makes a city. Certainly most recent successful redevelopments use a similar understanding. Within this view the gateway becomes relevant as one element making up the whole concept of the city, though today it will be in a very different guise. An appropriate answer now will not always be on the outside edge of the city, and has to represent the many different ways we approach - by train, car and bus, and elsewhere by air.

A city wall with gates is a contradiction of modern life but boundaries demarking areas of difference is not. Boundaries are not defensive or negative barriers but lines of agreement about change and exchange between one side and the other.

The openness of the modern city is not compromised or reduced by this because selective conditions can be established 'within' which are inappropriate 'without'. Winchester has walls within the walls, the Cathedral close, the College, the Prison. And of course one's own front door is the final threshold to cross from one world to another.

What if the central area of Winchester, say a little smaller than the line of the old city walls, was to be pedestrianised, ie determined by the behaviour pattern and pace of people on foot. Then gateways at points of entry would be important, primarily to proclaim that this area was governed by different, people-based rules, and under these rules only allow entry of vehicles with reason to be there. The boundary of this area is the location for the inner city car parks of "Park and Walk" and where to catch a bus. And within, a clearly understood precinct of smooth level paving and trees, signified by gateways.

Driving into Winchester all signs lead to car parks. Residents excepted, these are the termini, where one confronts the City for the first time. For rail travellers the terminus is the station, which stands at the top of a public forecourt of almost theatrical potential. It is a natural candidate as the first city gateway. But it does need to be celebrated as such and connected to the centre. Car parks on the other hand seem a long shot as contenders for the title, Gateway to Winchester, as they are usually treated as an embarrassment to be pushed to some derelict waste land. On the other hand if they were designed to have the significance of a city gateway, they would realise the important reality of arrival.

Park and Ride locations could be 'Termini' or 'Ports of Entry', with all the possibilities of, transport interchange facilities, safe supervised parking, cafe, and more. Here is the opportunity, to arrange efficient, land-saving, multiple layers of cars within what could be a majestic wall, a city wall as car park, car parks which make a new city wall. (Fig 2) Locate on the outer boundary, they would landmark entry to the City. With shared parking they would be an ideal partner for super stores. Tesco's is marked by an illuminated tower. What marks entry to the City ?

Notes 1 & 2 from Invisible cities, by Italo Calvino