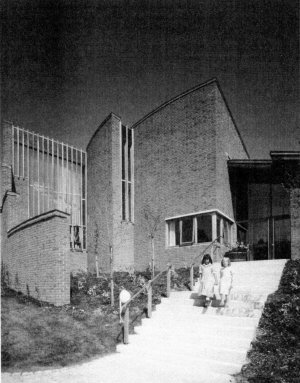

Solent Infants School, completed 1994

(Portsmouth Society Award 1995)

Photo by Peter Durrant

Architectual Authenticity - TrustNews Sept 17

Reply to Robert Adam’s “Architectural Style” (TrustNews, September 2017)

Robert Adam is at his most persuasive when he is pleading for sensitive contexturalism. Such an approach has long been part of the philosophy underling the designs of the best practices and was certainly well understood in the Hampshire County Architect's Department under Sir Colin Stansfield Smith, without recourse to the superficial emulation of past mannerisms.

Robert Adam complains that the “Modern Movement in architecture is international in character and therefore without authentic local roots. A visit to Fishbourne will convince anyone that architecture in UK has been international since at least Roman times. Indeed the palatial villa there was entirely unsuited to our climate, being based on a Roman model. The Normans imported their version of Romanesque as in Winchester cathedral. The more sophisticated and efficient gothic vaulting was first developed in France, the earliest example of which is seen at Bayeux c. AD 1150. Master builders came from France to build Canterbury cathedral and Caen stone was also imported for this and many of the important buildings in the Kent, Sussex, Hampshire Weald, where no workable building stone occurs.

Modernist architectural theory and practice has its roots in the industrial revolution. Some regard the Crystal Palace, May 1851 (a century earlier than Robert Adam’s date) as the earliest modern building in UK. That it was designed by an engineer, Paxton, rather than an architect, is no accident. Innovative cast-iron structures were built in the great ports of Liverpool and Glasgow. Pevsner cites Glasgow School of Art (1897) as one of the great early modern buildings of UK. pre-dating Frank Lloyd Wright's Unity Temple at Oak Park, Chicago.

Solent Infants School, Portsmouth, completed 1994 (Portsmouth Society Award 1995)Following the trauma and devastation of the First World War, the old hierarchical modes of operating were seen to be bankrupt and an obstacle to addressing the huge problems societies faced. The failure of humanity to address those disfunctionalities in the inter-war period is part of our tragic history.

Robert Adam chooses an unfortunate example in the House of Commons in seeking to defend the value of tradition. Many, myself included, believe that the medieval layout and trappings of the House has a malign effect and bear some responsibility for the ya-boo style of infantile, point-scoring debate which seems to make the search for reasoned compromise impossible. Compared with the Bundestag or the Scottish or Welsh assembly buildings with their amphitheatre layout, this is not a building in which forward-looking, adult diplomacy is likely to thrive.

I question also whether his declared aim, to cherish the specific identity of “place” is best served by what he calls “traditional architecture”. The sort of cosmetic camouflage he appears to recommend, with added pediments, fan-lights, cornices and colonnaded porches, in my eyes dilutes, diminishes and confuses the untrained eye as to our true tradition, of constant learning and innovation, making it hard to distinguish from nostalgic fakery.

I share with Charles Rennie Mackintosh a love of J. D. Sedding’s aphorism ‘There is hope in honest error, none in the icy perfection of the mere stylist‘.