Conservation in Winchester - TrustNews July 17

Winchester is the county town of Hampshire whose county council had extensive powers and large resources. After the second world war, they massively increased their office space in 1956 and again in 1966, demolishing the western edge of the walled city and two or three High Street buildings to bypass the bottleneck of the Westgate, at a time when the city centre had become very run down.

The City Council was an active independent authority which steadily built council estates and central housing so that by 1969, 50% of its housing stock belonged to the Council. They had a Town Clerk, City Engineer, Housing Officer, Architect and a Legal Department.

Both authorities regarded Winchester as ‘special’ due to its history and important listed buildings – the Cathedral, Winchester College and St Cross.

In 1946 the City had sought planning advice from Sir Patrick Abercrombie, who failed to adjust to the small scale of Winchester townscape. They proposed demolition of the Guildhall and historic buildings around it and 33 acres of ‘slums’ in the Brooks area for comprehensive development. In 1953, following a successful private member's bill in Parliament, St Georges Street was widened. Historic streets were degraded by car servicing and parking sites and vacant land appeared all over the central area. To his credit, the Town Clerk commissioned a retired government inspector of listed buildings to advise him on which listed buildings were essential to the Winchester character and this was to be published in the 1962 Garton Report.

ln 1957 residents were so alarmed at the tide of demolition that they created the ‘Winchester Preservation Trust’ to combat the proposals.

It is against this background that in 1957 the Govern-ment enacted the ‘Civic Amenities Act’ which required planning authorities to designate Conservation Areas to protect historic environments. The County Planning Department under the progressive lead of Roger Brown, published a Town Centre Plan the same year that both designated the Central Conservation Area, Hyde and St Cross, and adopted a modified version of the 1964 City Engineer's dual carriageway three-quarter inner ring road to solve the increasing traffic problem without knocking down any ‘listed’ buildings and to facilitate the pedestrianisation of a major part of the High Street. However, this plan had no visual assessment.

In 1973 the list of historic buildings was upgraded from 300 to 760, with 140 on a supplementary list, thereby strengthening the Conservation Area.

In 1974 there was a major reorganisation of planning powers and Winchester City was combined with two large rural districts, north and south, and given planning and development control powers. Under the leadership of architect/planner Jack Thompson, this brought together a team of officers with a very different outlook and range of skills, including the ability to test the impact of new proposals by perspective drawing. This coincided with the advent of councillors who opposed more demolition and expected a high standard of design in new buildings.

Challenges to the ‘conservation camp’ came thick and fast. Routine applications for large office buildings that would attract unacceptable traffic had to be refused. Some officers still tried to demolish more Victorian buildings by putting up raking shores to convince councillors that they were dangerous. Detailed plans and a seductive model for the three-quarter inner ring road (that would have added a large roundabout behind City Mill) were submitted by the City Engineer and rejected.

The first Government M3 proposals to remove a ‘national bottleneck’ were submitted and went to a Public Enquiry in 1975. Although outside the Conservation Area, it was so close as to dramatically affect the City’s setting, with 10 lanes of traffic and the attendant noise and cutting off St Catherine’s Hill from the Town. A proposed link road from Durngate to the M3 junction of Winnall with large areas of car parking at the southern end of Winnall Moors was rejected at a Public Enquiry as the result of vigorous local opposition. This paved the way for the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Naturalist Trust over succeeding years to upgrade the water meadows as an area of national scientific interest, north and south of the centre, and allow increased public access.

The City Council also created a major ‘design challenge’ through an application on railway land they had acquired for a 960-space multi-story car park, a glass-clad office building of 10,000 square feet and a 139-bed hotel with a car park. Drawings showed how these alien ‘layery' structures would have impinged on views all over the central area, which would have made quality development control on smaller sites very difficult. This was withdrawn.

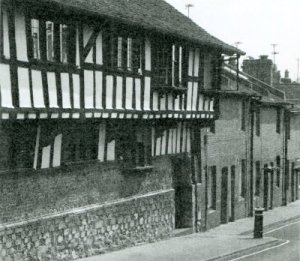

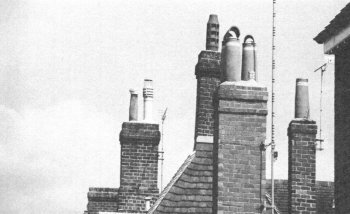

The control over demolition in Conservation Areas in the 1971 Planning Act made possible the rejection of one or two unsuitable applications already granted planning permission and to combat the demolition of chimneys. The Conservation Officer was able to reinvigorate the ‘town scheme’ partnership between Central Government and the two local authorities, negotiated by the previous Town Clerk which ran for 30 years, to repair many key listed buildings, including Gilberts Bookshop, the Square, 35 and 36 The Pentice, 106 and 107 High Street, St John's House, the United Church, No 1 and No 7 The Close, the Close Walls and St John’s Church Hall.

However the City is not a ‘museum town’ so there was some further demolition of unlisted buildings for replacements whose design and use would enhance the Conservation Area. For example, the ugly, flat-roofed Woolworth store was replaced by a range of shops with attractive pitched roofs.

The 1962 electrification of the railway helped to boost confidence in residential investment and pushed out car servicing uses to Winnall. The Conservation area was extended in 1989 to include St Giles Hill, Christchurch Road, Orams Arbour, linking with St Cross and surroundings to Winchester College, and again in 2003 to include more residential areas at Hyde and Highcliffe. In 1989 the Barracks was re-sited to Littleton, removing the noise and danger of helicopter flights from the centre, eventually paving the way for a Conservation Scheme for the upper and lower Barracks to be implemented in the 1990’s.

Was the Civic Amenities Act useful? The answer must be yes - not only in Winchester but also in the district towns. Canon Street and St John’s Street were saved. Eastgate Street and North Walls were restored with much historic townscape including the Theatre Royal and many good quality new buildings erected. The riverside walk has been upgraded. However, the City boundaries were still drawn too rigidly.

In 1988 the M3 was re-sited to a more sensitive route releasing land for the two new well-landscaped Park and Ride sites. It is once again possible to walk and enjoy cycling or walking across the old railway viaduct from the Southern Park and Ride site into the heart of the City.

What of the future

The car and East/West communications remain an unsolved problem together with the bus services. The future of Silver Hill regeneration area is in the balance and it appears that City Councillors are no longer valuing the potential economic value of 20th Century buildings to the local economy, as evidenced in the demolition of the Fire Station. For political reasons, they are encouraging buildings which are out of scale and character, such as an elderly housing scheme in Chesil Street, and there is pressure for overlarge office buildings near the station.