The Waterways of Winchester - TrustNews Spring 1994

By Elizabeth Proudman who is a Winchester City Guide, a local historian and longstanding member of the Trust.

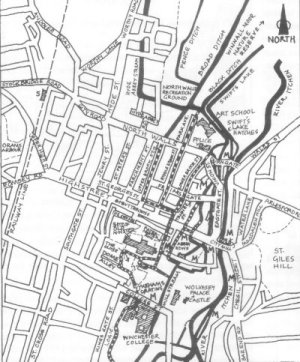

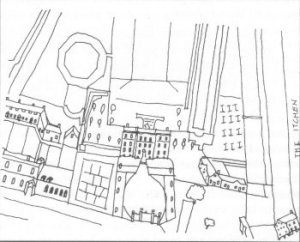

Map and drawings by Kate Proudman.

Hampshire has some of the loveliest countryside in England. The downs are called 'open spaces' for recreation in the 1990s, and the rivers 'high quality amenities', and their natural beauty delights us in our leisure activities. We walk or fish for trout, watch birds or canoe, and admire the scenery under the ever-changing sky. It is easy to understand how Keats was inspired to write poetry here as he walked from Winchester to St Cross. "Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness" he wrote in Winchester in 1819, and he said that the good air was worth 6d a pint.

The clear, fast-flowing streams of the chalk have shaped our landscape. As times have changed, so has our use of the rivers. Three thousand years ago people may have watched amazed from Hengistbury Head as the stones for Stonehenge were floated up the Avon. The Earl of Southampton who once entertained Shakespeare at Titchfield on the Meon, would be surprised to see the Sunday evening traffic jams on the River Hamble in the late twentieth century as the weekend sailors come home. The Saxon nuns might not recognise their Broad Lands on the Test either. But whether it is the great families who built houses for pleasure like the Brydges at Avington on the Itchen, the Cistercian monks who sought tranquility on the Beaulieu river, the Portals making paper at Laverstoke on the Test, or the Saxon Kings with their palace in Winchester, they all settled where they did because of the water.

Winchester sits in a valley, to the west of the River Itchen. When the Isle of Wight was still part of the mainland, the Itchen was merely a tributary of the larger River Test, which flowed into the River Solent. But for thousands of years now the Itchen has been a river in its own right. It is tidal up to Woodmill, and the National Rivers Authority is "guardian of the water environment" and responsible for all its aspects. Southern Water abstracts 10 million gallons a day from the river at Otterbourne, and the same again at Gaters Mill, near the M27 crossing, as drinking water for the 250,000 people who live in its catchment area. The water quality for the whole length of the river is described as 'good', Class 1A above Eastleigh, and Class 1B below, even though Eastleigh Sewage works pumps out 6.6 million gallons a day into the river!

The River Itchen

The Itchen has three main tributaries: the Arle, the Cheriton Stream and the Candover Stream which join west of Alresford and flow on through Winchester and down to Woolston. The springs come from the chalk aquifer and the water is always clear and clean, always fast flowing, and the temperature is constant - about 50 F - excellent for trout and watercress, but too cold for modern-day swimmers. For most of its length the river consists of several different streams meandering through the valley, a result of man's use of the water through the ages. Drinking water and drainage were important, of course, but the water also was used as a power supply for local industry, for mills, for transport, and later for water meadows. A fourth small stream joins the Itchen near Headbourne Worthy Church, and was the water supply for Hyde Abbey and for Hyde Mill.

Just west of St Giles' Hill there is a gravel spur across the marsh of the valley, and here a prehistoric trackway forded the river. There are remains of iron age enclosure north of the High Street from Orams Arbour down as far as St Peter Street, but it seems likely that the area of the present city of Winchester from Parchment Street down to the river was an uninhabitable marsh in prehistoric times. When the Romans came in 43 AD they used the same ford, fortified it and founded Venta Belgarum. Little detail is known of how they drained the valley, although wooden Roman land drains were found in the Brooks excavation in the summer of 1988, and then a Roman watergate was discovered near Durngate in the winter of 1988-89. Venta Belgarum was the fifth city in Roman Britannia, and must have had a bath complex somewhere. It would be good to think that the archaeologists might discover it one day, but perhaps it is under the Cathedral! Traces do remain of what could be a gravity-fed aqueduct bringing drinking water from Easton Down.

King Alfred

Map showing Winchester's Waterways

It is with the Anglo-Saxon kings of Wessex that we know anything for certain. Alfred became king in 871. Winchester was the largest of his fortified towns, the burghs, listed in the Burghal Hidage. He reconstructed the Roman town wall which by then was in a ruined state. The 1988 excavations at Durngate showed the Anglo-Saxon masonry built on top of the remains of the Roman wall. It enclosed a town of 143.8 acres, and Alfred made Winchester his capital. The High Street is today slightly (16m) to the north of the Roman line, and maybe this is because the Roman Bridge fell and the river crossing was moved slightly upstream to avoid the turbulence caused. The new site of the City Bridge is credited to St Swithun (in the year 859). By Alfred's time the street plan of the city was much as we know it today. The Anglo-Saxons were not people who lived by choice in towns, but militiamen were needed to defend the town walls. It is said that it was to encourage the people to live in the city that Alfred had streams brought inside the city walls, to improve the amenities for the inhabitants. The story of these water courses is the story of Winchester. They still run - usually underground today - as they have for over 1,000 years. They have given their name, the Brooks, to the new shopping centre.

From time immemorial the river has been divided into two streams under Easton Down, near Easton church, almost certainly by the hand of man. The river itself runs to the east of the Winnall Moors nature reserve, and then close under St Giles' Hill. To the west, in the North Walls' recreation ground, is the diversion tradition attributes to King Alfred, flowing in several strands. Beside the bowling green is the Black Ditch, and parallel to it is Swift's Lake. These two flow together behind the Art School to a sluice called Swift's Lake Hatches. It was from this point that Alfred's stream was controlled and one branch flowed into the walled city across the modern street called North Walls between Durngate car park and the police station and continued along Lower Brook Street and Tanner Street. The other branch provides the moat to the Art School library today and then flows under Middle Brook Street. It was necessary to have a stream of water on slightly higher ground for water to run along Upper Brook Street, and the two drainage ditches across the middle of the recreation ground, Broad Ditch and Fence Ditch, provided a sufficient head of water for that.

There is considerable evidence that these streams date back to the ninth century. Documents survive describing the property of Alfred's widow, Ealhswith, and early in the tenth century charters show that mill feats were important assets of the New Minster and the Nunnaminster. The Black Ditch is mentioned as a boundary on an estate map of 961. These brooks, built at the time of Alfred at the end of the 9th century were still open streams at the middle of the 19th. A painting of Middle Brook Street in 1813 by Samuel Prout shows a somewhat idealised view of the "Joyous Streams" as they were called in earlier days. These streams - the Brooks - joined in St George's Street and flowed together across the High Street beside Cross Keys Passage. Until recently you could look down gratings on either side of the street and see Alfred's Brooks still running. Sadly. with the paving of the lower part of the High Street. these gratings have been covered over. But the stream is still there. One thing that has gone, I am glad to say, is the large public lavatory called the Maiden Chamber which stood on St George's Street near the present Marks & Spencers in the period from 1362-1600. In 1362 a man called John of Byketoun removed two apertures to enlarge his garden, and a few years later a monk was charged at the City Court for having taken away a seat 'to the damage of those living near'!

Upper Brook Street in medieval times was known as Sildwortenestret which meant Shieldmakers Street. (Perhaps the Heritage Centre should change its address!) By the fourteenth century the stream which ran along it was called Kingesbroke. This name probably means that it provided water to the Norman royal palace which stood near the Buttercross, and its Anglo-Saxon predecessor to the south.

Alfred's Brook runs under the High Street to the Forte Crest Hotel car park. This was the monastery area. Soon after Alfred's reign there were three minsters in Winchester: the Nunnaminster, the Old Minster (the Cathedral Priory of St Swithun) and the New Minster. Alfred's Brook was used by the Cathedral priory and the New Minster. You can clearly hear it flowing if you stand on the manhole cover outside the hotel. Here was a junction and the water was taken into the grounds of the New Minster to the west and the Cathedral priory to the south. The New Minster branch was blocked when the abbey moved to Hyde in 1110, but Aethelwold's Conduit, or the Lockburn as it is sometimes called, still runs.

Aethelwold's Conduits

St Aethelwold was bishop of Winchester from 962-984 in the reign of King Edgar, (and the man responsible for moving St Swithun's remains and causing the forty days of rain). He introduced the Benedictines to Winchester, monks who followed the Roman example of cleanliness and order. He rebuilt the cathedral, and the monastic buildings. On the anniversary of his death (1st August) prayers are said for St Aethelwold in the Cathedral. He is described as:

"Rebuilder of the second minster, maker of conduits, lover of music"

It is important to have good drains before you can appreciate the music! Wolfstan the Cantor, a monk who knew him wrote:

"He brought here sweet streams of fishful water, and an overflow of the stream passed through the inner part of the monastic buildings, cleansing the whole monastery with its murmur" and "He built all these dwelling places with strong walls. He covered them with roofs and clothed them with beauty"

Aethelwold's conduit still exists. The water flows under Paternoster Row, past the east end of the Cathedral to the sluice in the path beside Paradise, and the site of the Chapter House. There it divides, and one branch goes off across the Close where the cloisters were. The other went through what is now the Dean's garden where the monks' lavatorium was and flows in a rectangle under the necessarium. This was excavated in 1859 and was found to be a 46-holer. I am not sure why it was so large because there were never more than 60 monks! From there it ran into the mill stream which divides the dean's garden from the bishop's. This is the same stream which flows across the Abbey Gardens. The other branch flowed behind the houses on the other side of the Close, past No 11, the Pastoral Centre and Church House, to Dome Alley. Its presence there seems to indicate that this might have been the site of the monks' infirmary. Until 1884 it ran past the judge's lodging. But the fall of the land was not great enough to make this stream flow properly, and it became a series of stinking cesspits. The judges' health demanded that it should be diverted across in front of what is now the Pilgrims' School instead. Many people probably remember the Lockburn, as it was called, which flowed across the entrance to the school yard until it was covered over in 1977. From there it crosses over to College Street to provide a nice "sweet stream" round the domestic buildings of Winchester College, but the word `Lockburn' means dirty water, and the grating here has great significance for Winchester.

William of Wykeham

The Water Gardens of Henry Penton's House near the Eastgate,

after William Godson 1748

Middle Brook Street in 1813, after Samuel Prout

When William of Wykeham planned his new college he needed land and he wanted to build it just outside the priory grounds on a field called Dummersmead. This was a recreation area used by the monks, however, and they were not happy to lose it, especially when Wykeham demanded that the monastery provide a grill over the stream where it entered his college grounds from the monastery (and before that the town, of course) and that a man be employed to catch

"the offending dung, carcasses and putrid entrails"

that became trapped there. There was bound to be trouble. I have never heard that there was any difficulty in finding someone who was prepared to do this unattractive job, simply that the monastery did not want to pay his wages! Anyway a court case ensued which was not resolved until 1394, by which time Wykeham had been bishop for 30 years. In that time no work had been done on the nave of the Cathedral which Wykeham's predecessor, William of Edington, had begun to modernise in the 1350s. If Wykeham had not had this trouble over the grill he might have had time to finish his project and alter the Norman transepts of the Cathedral as well as the nave. How lucky he didn't!

In spite of the grating across the stream it never ceased to trouble the College. A wall was built across Outer Court in the sixteenth century to protect the Warden and Fellows from the noisome ditch. It is the same watercourse, called 'Logie' by the College, and the polluted water from the town continued to cause problems until main drains were built for the city in the nineteenth century.

By the fourteenth century it is known that the cathedral priory and Wolvesey Castle had stone conduits with lead pipes bringing fresh water for drinking from Easton, and a town pump was erected near the Butter Cross to impress Queen Elizabeth I when she visited Winchester in 1591 (for which work Francis Porke was paid eleven shillings). It is still in place in a photograph of 1850. But most private houses in Winchester in the middle ages got their water from wells or the open water courses and this went on until the 19th century. From the fifteenth century records exist of ordinances issued by the Burgh-mote which were designed to keep the streams clean: 'if any man cast any donge, straw, dede hogge, dogge or catte or any other fylthye into the water wherby the water mought be stoppid' he should be fined twelve pence' for example. But abuses were constant.

The first detailed map of Winchester was made by William Godson in 1750. He shows the mill stream leading to Abbey Mill running down the centre of the lower High Street, before it was widened to become the Broadway' at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Slightly to the west in the High Street between Middle Brook Street and Lower Brook Street there is another stretch of open water, unconnected to this mill stream. This is Merwenhay, and records go back to the twelfth century when it was dug to relieve the problems of flooding in the lower part of the town. There are the beautiful water gardens of Mr Penton's house shown too which stood in the Friarsgate area before Eastgate Street was built in the 1840s.

Gradually many of these old watercourses were covered over, and with the coming of the railway in 1839 and the waterworks at the top of St James Lane, there was clean piped water available - for those who could pay. But Alfred's Brooks and Aethelwold's conduits were the only drains Winchester had until 1875. That is another story.

Elizabeth Proudman will continue this story in the Summer Newsletter, and on Thursday 24 March, she will give a slide lecture on The Waterways of Winchester at The Milner Hall, St Peter's Street, to which members and guests are invited.