The Waterways of Winchester-part2 - TrustNews Spring 1995

Elizabeth Proudman's first article was published in the Spring 1994 Newsletter. She continues her story.

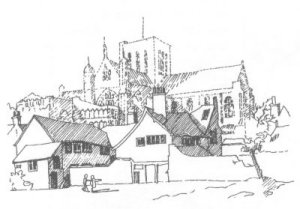

Drawings by Kate Proudman

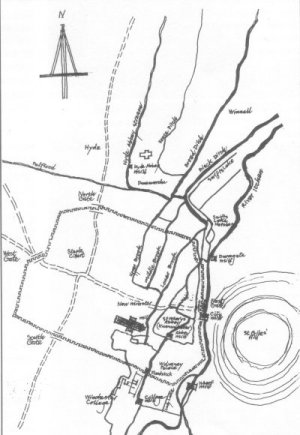

Map by Nick McPherson

When the Rt Rev John Milner wrote his history of Winchester in 1789 he began: 'As it is chiefly built on the gradual declivity of a western hill, and on dry soil, it is in general, cleanly and convenient to walk in .... The air, passing over chalkly (sic) hills and extensive downs, from whatever point of the compass it is wafted, is as untainted and pure as we conceive the atmosphere to have been originally created.... The waters, whether drawn from the bowels of the earth, or those that intersect and cleanse the city in various rapid streams, are as pure as the air and nearly as transparent Winchester is one of the best adapted spots in the kingdom for the residence of the human species.' That is a lovely description, but Milner's comments do not always quite agree with some other early evidence about conditions in Winchester!

The rain that falls in chalk country in the winter takes several months to soak through and reappear in the rivers, so they flow steadily even in dry weather, and these fast, even chalk streams were ideal for turning mill wheels. In the Domesday book 300 Hampshire water mills are mentioned; 98 were still working in 1900, and 34 in 1939. Many mills were small, serving their local community and they came and went as the years passed. Wooden mills were often destroyed by fire, but even the big stone water mills gradually fell out of use. Abstraction of water for a growing population, our love of fine white bread, and imported hard winter wheat from the US all contributed to their demise, and the last traditional water mill on the Itchen stopped work in the 1960s.

Map showing Winchester Mills

However, many mill leats and ponds survive. Other old streams which can still be seen in the valley are remains of watermeadows. For over 300 years men called drowners constructed a sophisticated system of channels and hatches in the valleys, and they carefully flooded the meadows each spring, with the warm river water rich in nutritious silt. Few water meadows are 'floated' any more because of the cost of labour and the availability of modern fertilisers, but many of the channels remain. Even the peaceful sport of fishing has changed the natural landscape. The weed is cut, the river gravel is raked for spawning, and the banks are planted to improve the fishing. The Itchen and its valley even in its most rural stretches has always been a man-managed environment.

John Keevil explained in the Summer Newsletter, that Saxon charters mention mills and mill streams in Winchester. In 901 the New Minster owned a mill inside the city walls, and there were already three mill streams beside Nunnaminster (where the Abbey Gardens are today) before that. By 1208 there were 22 mills between Hyde Abbey and St Cross, nine in Winchester itself. Six of these were built on the river but outside the city walls and they were thus in the Bishop's liberty known as the Soke, and their rents and profits were payable to him. The most lucrative was Durngate Mill, demolished in the 1960s, but Segrim's Mill (or Wharf Mill) along the Weirs, and Floodstock (on the City wall in College Street) brought good returns too. Milling was a profitable business. The City Mill goes back to 940 and it belonged to the nuns of Wherwell from 1086, until the Reformation.

Mostly the water was used to grind corn, but Winchester's water was used as power for parchment making, tanning, leather working, paper, and when Mary Tudor gave the Abbey Mill to the city in 1554 it was being used as a grindstone factory. (Its present function as the Environmental Health Office sounds suitably much more environmentally friendly!)

But far and away the most profitable activity in the city in medieval times was the wool and cloth trade. Between 1326 and 1363, when Edward III moved the market to Calais, Winchester was a town of the Staple - it had a licensed wool-market. The Staple Court was just inside the Westgate, to the North of the High Street. It didn't survive very long and by 1400 the 'Staple Garden' was described as a rubbish tip.

Durngate Mill

Twenty master weavers and 17 fullers formed a guild in 1577. They and the dyers worked mainly in Lower Brook Street, Tanner Street and Busket Lane and they disposed of the filth they produced in the easiest way possible-into the river. They stretched their cloths to dry on tenter hooks, wherever there was vacant land. Fullers finished the woven cloth. In the early days they felted it by first soaking it in vats of stale urine which they bought in the morning in the town, and then trampling on it with their feet. The workers must have welcomed the invention of fulling mills which used water-powered hammers and fullers earth instead! Fulling brought enormous rewards for the bishops with mills in the Soke, but there was no fulling mill inside the city walls until the early 1400s when the city constructed a mill at its own expense on the island known as Coitebury, (where the Friarsgate medical centre is today). It should have brought revenue to the townspeople, rather than to the Bishop, but sadly it was built when Winchester's wool trade had begun to decline. The flow of water was not strong enough to drive it adequately, and before long the mill was abandoned. The stream remains today; it flows through the Friarsgate flats, round the medical centre, beside the bus station and under the High Street, before running along in front of Abbey House.

The City Pump by the Buttercross

The cloth trade affected the suburbs too, especially where the ground was damp. In sixteenth century Fulflood the dyers were growing woad, saffron and madder, and the fullers were growing teazels. Outside the Southgate linen drapers had plots where they grew flax. As the cloth trade declined in Winchester, St Giles' Fair which had contributed so much to the prosperity of the city declined too. In the Black Death about half the population died, and this loss was not made up by the time Henry VIII dissolved the three great monasteries. The population fell from around 11,000 at its height in the eleventh century, to about 3,000 at the outbreak of the civil war in 1642. But the mill streams and King Alfred's Brooks continued to flow through the streets of Winchester, and very useful they were too.

The nice clean water to the north of the city was used by the brewers for their beer, and further down stream by everybody else, for drinking and cooking as well as various industrial purposes. The problem was that everyone threw everything they didn't want into the water. In the fifteen and sixteenth centuries the Burgh-mote spent much of its time trying to keep the city clean and healthy. By 1543 it was the responsibility of everyone whose property abutted the stream to scour its bed. From 1554 the Brooks were stopped for ten days in May every year, for the cleaning to be done and you could be imprisoned for failure to do your bit of Brook.

There were strict rules too about the disposal of rubbish. Shoemakers were only allowed to burn their scraps of leather between 9 pm and 4 am. Butchers were forbidden to throw 'intrayles or other vile things in the river of the Cytie... but onlie in the place called abbies bridge and there nother but where the same intrailes and other vile things be cutt iiii inches longe'. Dyers were fined 6d if they threw their slimy 'wodegore' in the river 'after the sone risinge in the morning'. There was a public washing place in Colebrook Street, but glovers could not use it or hang their skins out in the street. Within a hundred yards of the High Street you were forbidden to grind your wode, or keep your pigs or your dung heap. The fish shambles were up by the Westgate, beyond the butchers and the slaughterhouses in St Peter's Street. The fishmongers threw their waste into the street - but they had to throw two buckets of water after it.

I don't know how successful all these measures were because the Venetian ambassador who came to Winchester for Mary Tudor's wedding in 1554 wrote: 'They have some little plague... well nigh every year ...the cases for the most part occur amongst the lower classes, as if their disslute mode of life impaired their constitutions'. I think it was more likely to be the filth of their streets!

People had to pave the street in front of their house, or clean up any 'ded dogge ratte or horse' they found there at least once a week. In 1577 some of the smaller lanes were described as 'very fylthye and noifull to all such as shall passe by the same' and so it was 'agreed that all persons of or above the age of twelve years which shall doo his or her needes of easement meete to be done in pryvies...in any streate or lane of the sayed Cytie...shall forfayte and lose for every time vi d'. Informers were well rewarded, but the fact that these ordinances had to be repeated year after year suggests that the streets remained foul.

County Hospital, Colebrook Street 1732

There were several medieval public latrines in Winchester, sensibly built over King Alfred's Brooks - the largest was the quaintly-named Maydenchamber on St George's Street, near the present site of Marks and Spencer. Along the populated High Street stone-built cesspits had to be emptied regularly, but many people used unlined holes in their gardens. For drinking, the old monks and nuns had had water brought in lead pipes from the fresh downs at Easton, as had the Bishop at Wolvesey. But ordinary people could only dip their buckets in the river or the Brooks, or they could use the town pump near the City Cross unless they were lucky enough to have wells in their own gardens.

So it went. The population was small and there was plenty of open space even within the walls of Winchester. Plagues and sweating sickness and epidemics of flu came and people died. In bad times pest houses were built outside the walls where victims were kept in quarantine. People accepted the conditions they had always known.

Claims of modern marketing men are nothing new. In 1630 the Mayor, John Trussell, praised his city. He wrote:

"The purity of the ayre is such that neithere physician, apothecary nor surgeon did every grow rytche by their practice in this place."

Pavement Commissioners were appointed in 1771. They had wide powers to clean the streets, and control abuses. Unfortunately, the men appointed were usually learned divines, honest of course, and well-intentioned, but quite out of touch with the tradesmen of the town who were the rate payers. The College, the Dean and Chapter and the Bishop did not have to pay rates. Little agreement could be reached on reform, and the Brooks, King Alfred's ninth century streams, were the only system of drainage that Winchester had when the great population explosion arrived.

In Winchester in 1801 there were 5,000 people. In 1881 there were 19,000. This growth happened partly because of the arrival of the railway in 1839-40, and partly because the agricultural depression drove people to seek work in town. The poor people still lived in the Brooks area, and they took in lodgers to make ends meet. Up by the railway the water-works was opened, then the Union Workhouse was built. The prison followed, and soon speculative builders began to construct desirable residences on the airy western hill; the houses on St James Terrace, Orams Arbour, Clifton Terrace for example. These were all built with piped running water, but no main drains, and when the cesspits overflowed - as they frequently did - the effluent ran down the hill into the Brooks, the slums and the river.

The County Hospital was opened in Colebrook Street in 1732 with 'Despise thou not the chastening of the Almighty' written on the wall. The founder Alured Clarke actually said that sin was the cause of sickness: 'A Profligate state of life (eg sickness) was the result of unChristian living', and he said 'Unfortunately the poor are very incompetent judges of the true use of money'. In 1752 a larger hospital was built slightly uphill in Parchment Street and it poured all its wastes into cesspits too. There were serious epidemics in Winchester in the 1830s, whether of Asiatic cholera or not is disputed, but the people died just the same. Winchester doctors began to write to the papers to press for sanitary reforms, insisting that dirty drinking water and lack of sewers and not sin was the major cause of sickness. In 1850 the life expectancy in England as a whole was 58 years, in Winchester it was 50 and in the Brooks area it was 42 years.

The state of Winchester became a national scandal, but still nothing was done. What had been good enough for almost 1000 years was still good enough for some people.

When cholera threatened yet again in 1849, Bishop Sumner called for a day of prayer and humiliation, just like his predecessor Bishop Edington who had sung penitential psalms at the approach of the Black Death in 1348. The prayers didn't do much good on either occasion. In 1851 the student teachers had to move from their college at Wolvesey Palace because of all the sewage which `Winchester's Cleansing Streams' brought into the garden. A report appeared which spoke of babies playing on floors in the Brooks area where the effluent seeped up between the stones. As indisputable proof was finally found that epidemics were caused by drinking infected water the council was divided into two camps: the Muckabites who refused to raise a 6d rate to build a sewage system, and the public-spirited Anti-Muckabites led by the doctors, who believed it would be money well spent. In the council elections of 1861 the Muckabites won yet again, and their triumphant song was sung:

Good health to all the Muckabites

Heigh Ho! Stink 0!

Who love to have their Dirty Nights.

Heigh Ho! Stink 0!

Our cesspools shall not be Drained

Heigh Ho! Stink 0!

Our slush-holes shall be retained.

Heigh Ho! Stink 0!

As for fevers, we don't fear

Heigh Ho! Stink 0!

So long as we can get strong beer,

Heigh Ho! Stink 0!

Nor yet for Cholera do we care,

Heigh Ho! Stink 0!

The threat of cholera waned, and lethargy took the place of fear, but central government began to press for action, and threatened to impose a sewerage plan on the city for which Winchester would be obliged to pay. Finally the reformers won the day led by Dean Gamier and Freddie Morshead, the mayor, who was also a housemaster at Winchester College. In 1875 a main sewer was inserted from North Walls to Bull Drove and the Gamier Road pumping station was opened. Winchester is the only city I know of to have its sewage works named after its Dean, and to him we owe our cholera-free city and the lovely clear river in Winchester today.

On 12th August 1819 John Keats came to Winchester, before the bad times came. He wrote to his sister "It is the pleasantest town I ever was in, and has the most recommendations of any. The whole town is beautifully wooded. From the hill at the eastern extremity you see a prospect of streets and old buildings mixed up with trees. Then there are the most beautiful streams about I ever saw - full of trout." He said that the air was so good it was worth 6d a pint! I wonder how he and Milner would like Winchester today. Have we cared for it well? Is it still one of the best adapted spots for the human species?