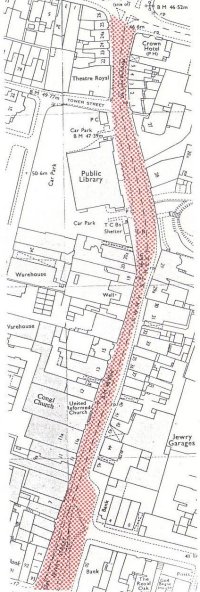

Jewry Street

Controls

The appearance of buildings is affected by the planning controls and building regulations in use at the time. There have been such restrictions over several centuries so that houses in the 16th century, for example, could be taxed if a gable fronted the street.

A tax of £5 in goods would be levied to enlarge private houses and owners considered baths, casement windows and panelling as removable fittings. The vertical sliding sash window was introduced from Holland. In the 17th century there was excise duty on glass, the tax on the number of windows, if more than six, being based on the house rental of £5 per annum minimum.

Poverty in the town could be assessed by the amount raised from a hearth or stove tax of two shillings each. The 18th century introduced a tax on bricks of 2s.6d. per 1,000 which seemed to result in the popular tile and slate hanging to evade the tax. Tiles were even made to look like bricks, though bricks in the mid 18th century only cost 20 shillings per 1,000 (Essex facing bricks for Sheridan House, in 1983, cost £150 for that number).

The traditional English bond brickwork gave way in the mid 17th century to the more economic Flemish bond. Herring Bone pattern brickwork is adapted to the timber framing of the Elizabethan Restaurant (rebuilt 1920s).

The 1696 window tax was repealed in 1851 during Queen Victoria's reign (1837-1901). The price of glass dropped from one shilling to tuppence halfpenny a square foot, resulting in larger window panes and fewer glazing bars. The Crystal Palace exhibition halls used the largest pane at that time, of 49" x 10".

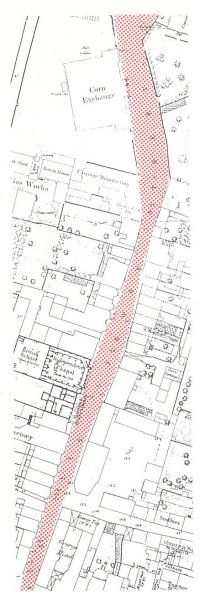

The George Hotel, Jewry Street 1871

Official controls in the 1980s start with fees on a sliding scale when drawings are submitted for planning and building control approval. There can be conflict between the wishes of the individual owner wanting freedom of expression and the requirements of the local authority.

The contentious issue of colour control engenders a lively debate, particularly when frontages, as seen at Nos. 6, 28 and 38, are painted out of keeping with the street scene. The City Council produced a booklet in 1976 on "Signs and Shopfronts" to give guidelines on shop fascias and signs. Attractive shop signs in this street are conspicuous by their absence.

An analysis of types of shops in previous centuries produces a clear image of a different and slower way of life. The Jewry Street tobacconist who, in the 19th century also had a billiard saloon, would be popular with pipe smokers and those who enjoyed a game of billiards by the hour (the 1983 version is the snooker hall). High city rates, apart from cigarettes ousting pipe tobacco, meant that by 1909 there was only one such shop in the town. A specialist tobacco shop (from the Pentice) has now been re-assembled in the City Museum.

So coach builders, saddlers, coopers, ironmongers, chemists, florists, and fish shops in Jewry Street have been replaced by Building Societies and multiple stores and the professional people have moved to the High Street.

The encouragement of hire purchase, together with the fragmentation of family life, has produced a greater demand for house furnishing. With the loosening of financial and home ties have grown the second hand and antique businesses. In line with this is a lively interest in fashionable clothes by young people linked with a wish to eat out, there being eight such premises in the street.

The George Hotel, Jewry Street site

cleared for Barclays Bank